189: Cloudflare's Secret Sauce pt.2, Peter Lynch's Lucky vs Unlucky, Non-Practising Gamers, Genome Sizes, Zelda's Violin, Supply Chain Issues, and Blue Longhorn Beetle

"like the Escher drawing of the two hands"

To become different from what we are, we must have some awareness of what we are.

—Eric Hoffer

👋 Hey, I’m back! Did you miss me? I missed you!

I hope the little break allowed you to catch up on those unopened past editions in your inbox, haha ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

If you want to see some of the things I saw on my Canadian Thanksgiving break, I posted a thread of photos here.

It made me think about how the ‘halo effect’ also applies to photos. If people see nice photos, they assume you’re having a good time, without really knowing.

Something to remember when it feels like everybody else is having a better time than you are.

🎮 I consider myself a non-practising gamer.

Culturally, I’m a gamer, but I don't really game anymore. That may sound like a contradiction, but I think it makes sense.

There’s lots of people who don’t game because they were never interested to begin with, or did as kids, but lost interest.

I don’t fall into those categories.

Video games used to play a central role during my formative years, and my whole world was pretty much Doom, Quake, Starcraft, etc, for a while.

I was a map-maker and hosted LAN parties in my parents’ basement (pre online multiplayer, you had to bring your whole computer to someone else’s house and set up a local ethernet network… Most computers didn’t come with networking, so I had to open everybody’s computers, put in networking cards that my father had, install some drivers and set everything up with DOS command lines… I didn’t even read English back then, but I had somehow learned all the incantations. Command lines are their own language.. It’s a bit like if you listen often enough to a song in a foreign languages. You end up knowing it very well phonetically even if you don’t really understand the words).

Anyway…

Over time I kind of stopped gaming. For some years I still watched others play on Twitch (watching Shroud and Chocotaco play PUBG was my fave a few years ago), but even that is pretty much gone now.

I't’s mostly the opportunity cost — ever since having kids, my free time has been a lot more limited — and because I can’t help but feel that what I’m “building” and “grinding towards” in games feels kind of hollow now.

My video games are this newsletter and investing now.I’m still solving puzzles and gaining XP and levelling up slowly over time, meeting other “players” that become my friends.

But it feels better to build this world here than find some magical armor in some digital world. Closer to base reality.

I think a lot of the urges that made gaming fun — improving skills, mastery, exploration, accumulating cool equipment and resources, getting into a flow state, thinking about tactics and strategies, learning from more skilled players, etc — can be met by what I’m doing in investing and the newsletter, as strange as this may sound to some.

I suspect a lot of entrepreneurs who are/were gamers (like Tobi Lütke) may also see some parallels between the worlds of business and (some) games.

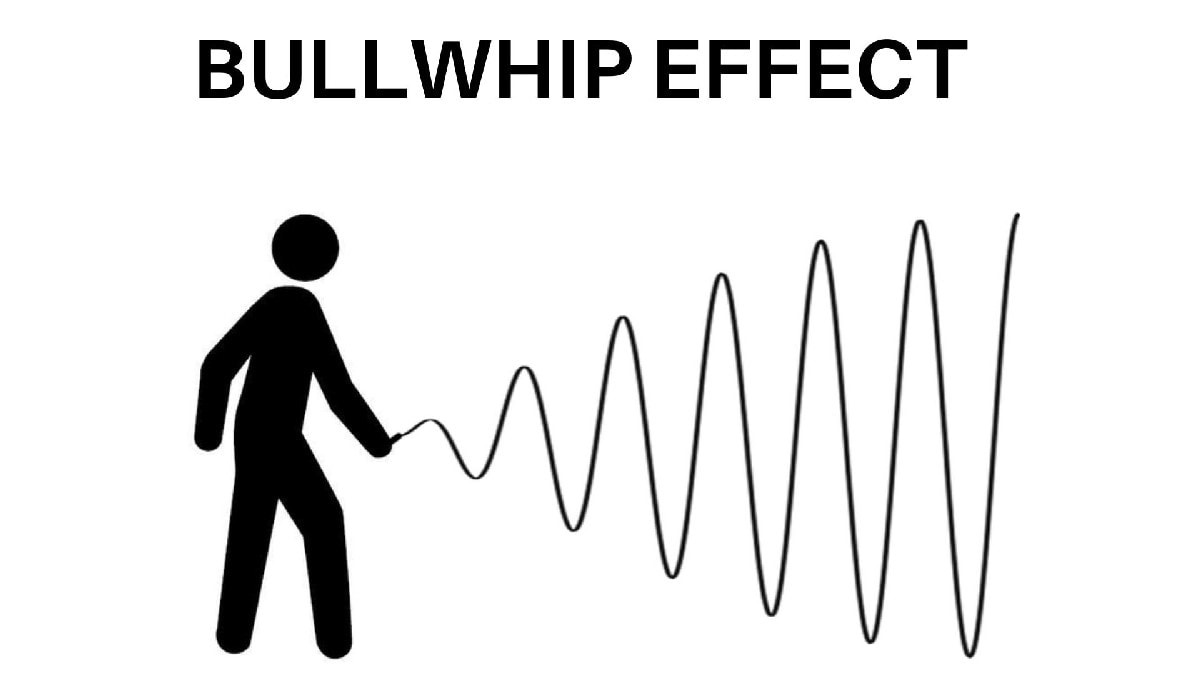

🌏 I now hear regularly from people in every day life about global supply chain issues (ie. “this sofa we ordered last year hasn’t shipped yet”, “there’s no inventory at dearlerships for that car I want to buy”, etc).

The pandemics is still making waves…

Thinking a bit farther ahead, I wonder if by the time people start to get used to this “new reality”, we’ll be pretty close to things going back to normal. In my experience, it’s often how things work…

By the time a phenomenon has played long enough for people to be ready to extrapolate it going forward, we’re getting pretty close to the end of it. Will this happen for expectations for energy prices or inflation or whatever? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

💚 🥃 Is this the one that convinces you to become a supporter? It’s quick and inexpensive:

A Word from our Sponsor: 💰Watchlist Investing 💰

Are you a value investor looking to expand your watchlist of great companies to own at the right price? Because what’s an investor without a good watchlist?

Watchlist Investing is a monthly newsletter devoted to studying great businesses and helping readers be ready to pounce when Mr. Market gets irrational (🤪).

You’ll get access to independent, bottom-up primary research, including Deep Dives, Quick Looks, and analysis of long-term capital allocation decisions.

Watchlist Investing founder Adam Mead spent over a decade in commercial credit, has skin in the game as a value investor, and is the author of ‘The Complete Financial History of Berkshire Hathaway’. 📕

Sign up here for just $199/year and get 10% off your first year with the coupon code “Liberty”.

Here’s a free taste with two issues from the back-catalogue:

Investing & Business

Peter Lynch’s Lucky vs Unlucky Investor (Market Timing)

Friend-of-the-show Tobias Carlisle recently posted a Peter Lynch quote:

Starting in 1965 if you invested at the peak of the market in each year, your annual return was 10.6%. If you timed the market perfectly, invested at the low point of each year, your return was 11.7%. The difference between great timing and lousy timing was only 1.1%.

This was published in 1995, so the study looked back 30 years.

It was updated here for the 1994 to 2020 period, and the results are relatively similar:

From 1994 to 2020, the annual-return difference between the absolute worst-timed unlucky investor, the absolute best-timed lucky investor, and a start-of-the-year investor in an S&P 500 fund was 8.7%, 10.2%, and 9.6% respectively—an annualized difference of only 1.5% between the worst-timed and an omniscient best-timed investor

My first thought is that this is a bit counter-intuitive. I would’ve expected a bigger delta between investing at the very top and the very bottom each year for that long, but then, there’s a few things to consider:

This is looking at an index of 500 companies, and that’s inherently less volatile than, say, a single company stock. So if you’re a stock-picker, the difference between the highs and the lows will be higher and the returns to a nice entry point will thus be higher.

We also have to remember that 1.1% or 1.5% compounded over multiple decades is still a meaningful amount. It sounds small when you say it as a percentage, but the cumulative $ amount at the end is pretty material.

This type of study also reminds me of the related ones about “what if you had missed the 10 best days, 10 worst days, etc”. Always a good reminder that it’s the waiting that matters most, not all the activity at the beginning and the end:

Cloudflare’s Secret Sauce, Part 2

This company is hard to keep up with… They release so many new features, so many blog posts to explain various things. Even as a casual observer it can feel like by the time I’ve caught up, there’s twice as much.

Here’s a few highlights from a recent post about “The secret to Cloudflare’s pace of Innovation” (I covered this back in edition #114):

how do we do it? How do we get so much stuff out so quickly? [...]

One of the core things we look for when hiring in every role at Cloudflare — be it engineering and product or sales or account — is curiosity. We seek people who approach a situation with curiosity — who seek to understand the what, the how, and perhaps most importantly, the why of the world around them. [...]

To innovate, we listen. One of the things I screen for when we hire product managers is their ability to listen and synthesize the information they are hearing and then their ability to distill it into actionable problems for us to tackle. We ship early and often with initial concepts. We must listen closely to the feedback from customers [...]

On one hand, this culture stuff — though extremely important — is hard to talk about on a high level because everybody is in favor of motherhood and apple pie, and bad companies can say the right things too. It’s more about implementation and small every day actions that matter.

But I did find this focus on curiosity and ability to synthesize knowledge interesting, as it’s not elements I’ve seen much before, and it does match what I know of the company.

The best dog food

We like to say Cloudflare was built on Cloudflare and for Cloudflare. This means we eat our own dog food with a glass of our own champagne on the side [...]

I love the model of a company that builds a platform on top of which is keeps building the company. It’s very much like the Escher drawing of the two hands drawing each other:

It’s driven by our Workers platform. This isn’t just something that’s making our customers' lives easier. No containers to manage; no scaling to handle. We use it, too. It’s a layer of abstraction on top of our network that enables a massive amount of development velocity. Our unified architecture provides a single, scalable platform on which to innovate and allows us to roll things out in a matter of seconds across our entire network (and roll them back even more quickly if things don’t go to plan, which also sometimes happens). [...]

This abstraction enables us to have smaller teams to build any new product or service. While others in the industry talk about building “pizza box” teams — teams small enough that they can all share a pizza together — many of our innovation efforts start with teams even smaller. At Cloudflare, it is not unusual for an initial product idea to start with a team small enough to split a pack of Twinkies and for the initial proof of concept to go from whiteboard to rolled out in days. [...]

This is clearly modelled after Amazon (though it’s not like Amazon has a monopoly on the idea of small, nimble teams).

We ship software for businesses like a consumer software company. Traditional B2B software development typically follows longer development cycles and focuses on delivering more fully featured and deeply integrated offerings out of the gate. [...] Consumer software, on the other hand, is typically built in a highly iterative process [...]

This is something that always stands out to me when thinking of this company.

Born to be free

Typically, in B2B enterprise software companies, the big customers and the multi-million dollar contracts get 99.99% of the focus. Here’s what I would say: our free customers are the secret sauce to our innovation. Today, millions of websites and applications across the globe use our service for free. Free is invaluable to innovation.

One of the most difficult parts of building B2B software is getting the first 100 users. These early users are critical to assess the quality, scale, and capabilities of a product. [...] We’re fortunate to have millions of free sites and applications on our network. Like a consumer app developer, we typically roll out new capabilities to pods of these users first. These users give us the volume and scale to get confident in what we’ve delivered. The more confident we get, the more broadly we roll out, such that by the time it hits broad rollout, our customers can feel confident in the quality and stability.

This can be hard to match for others, because everything has to be architected the right way from day 1 for this to work.

You likely just can’t open up the floodgates and let hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of free users flood into products that were designed for a few thousands of big paying enterprise customers...

You’re likely to find out real quick that you don’t have the right self-serve infrastructure, that your sales and customer service people are overwhelmed instantly and can’t service paying customers anymore, that your technical architecture has a bunch of bottlenecks and isn’t optimized for this and now costs a fortune to run, bringing down your gross margins, etc…

Science & Technology

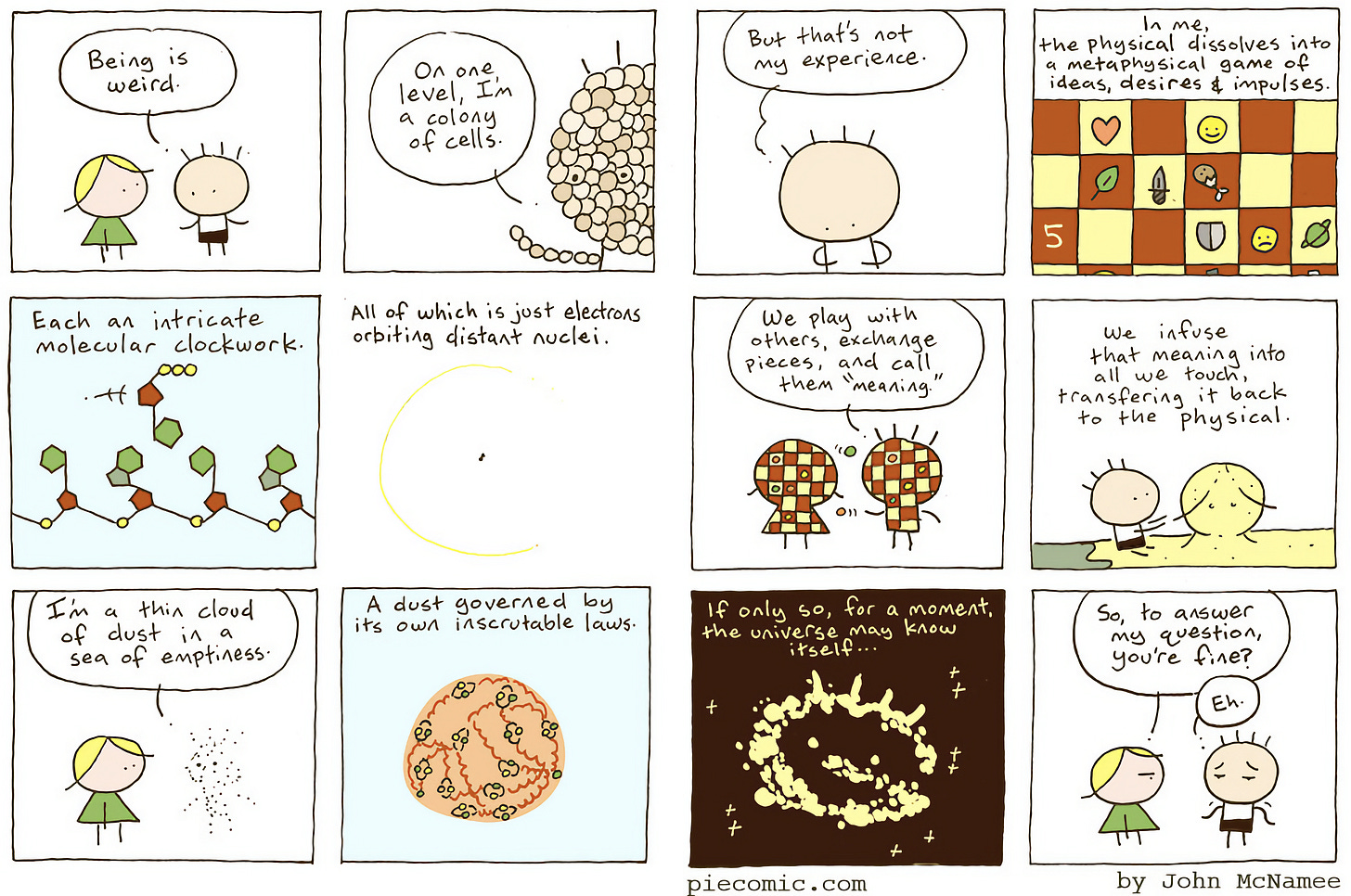

“Being is weird.”

h/t Visakanv

🧬 Salamander genome FTW 🦎

I’ve been reading ‘A Crack in Creation’ by Jennifer Doudna (who won the Nobel prize for her pioneering work on CRISPR), and found this passage interesting:

Most viruses, for instance, have just a few thousand letters of DNA (or RNA, since some viral genomes contain no DNA) and a small handful of genes. Bacterial genomes, by contrast, are millions of letters long and contain around 4,000 genes. Fly genomes contain around 14,000 genes spread out across hundreds of millions of DNA base pairs. The human genome comprises about 3.2 billion letters of DNA, with around 21,000 protein-coding genes. Interestingly, a genome’s size is not an accurate predictor of an organism’s complexity; the human genome is roughly the same length as a mouse or frog genome, about ten times smaller than the salamander genome, and more than one hundred times smaller than some plant genomes.

Look at those flowering plants! So much variability too (notice that the X axis, which shows genome size in base pairs, is logarithmic):

The Arts & History

The Evolution of Zelda Music (1985-2017)

This is simple: Rob Landes playing Zelda music through the ages.

As someone who grew up on a few instalments of the series, it always tiggers some nice turbo-nostalgia to hear.

Blue Longhorn Beetle

Thanks to Substack, I now have access to Getty Images. To test it out, I typed in a random keyword, and here’s the coolest image that came up. I hope you enjoy it, because hey, what’s not to like about a close-up portrait of a blue beetle.

Another great issue...just added the annual subscription. While there's always some good stuff in every update, the segment before subscription pitch is the heart of your Substack and where I get the most value. Really enjoyed both the photos comment and the gaming insights. Thanks for sharing!

Yeah, the "what if you missed the 10 best days" thing always bothered me. Take the converse and "what if you missed the 10 worst days"... The conclusion of harnessing the power of compounding by staying invested is a good one, but the "10 best/worst" days is a red herring.