Claude Shannon fan club with Jimmy Soni and David Senra (Transcript)

Transcript of Podcast #16

You can listen to the audio here:

Liberty:

I'm so happy to have two of my very good friends with me today. I think when most friend groups meet, maybe they talk about football or about fast cars or they go bowling or I don't know what people do. But we're a bunch of nerds, so today we're going to talk about information theory. Jimmy, David, thank you for joining me in the first official Claude Shannon fan club meeting, or as we say in French, Claude Shannon. I think there's so much to say, but at first, a good intro will be going around the horn and just talking a bit about how we discovered Claude Shannon and why we think he's special, why we think he's interesting. It's a good thing I'm not easily intimidated because I'm going to talk about a book with the guy who wrote the book and a guy who reads books for a living. So, Jimmy, how about you? Where did it start with Claude Shannon?

Jimmy Soni:

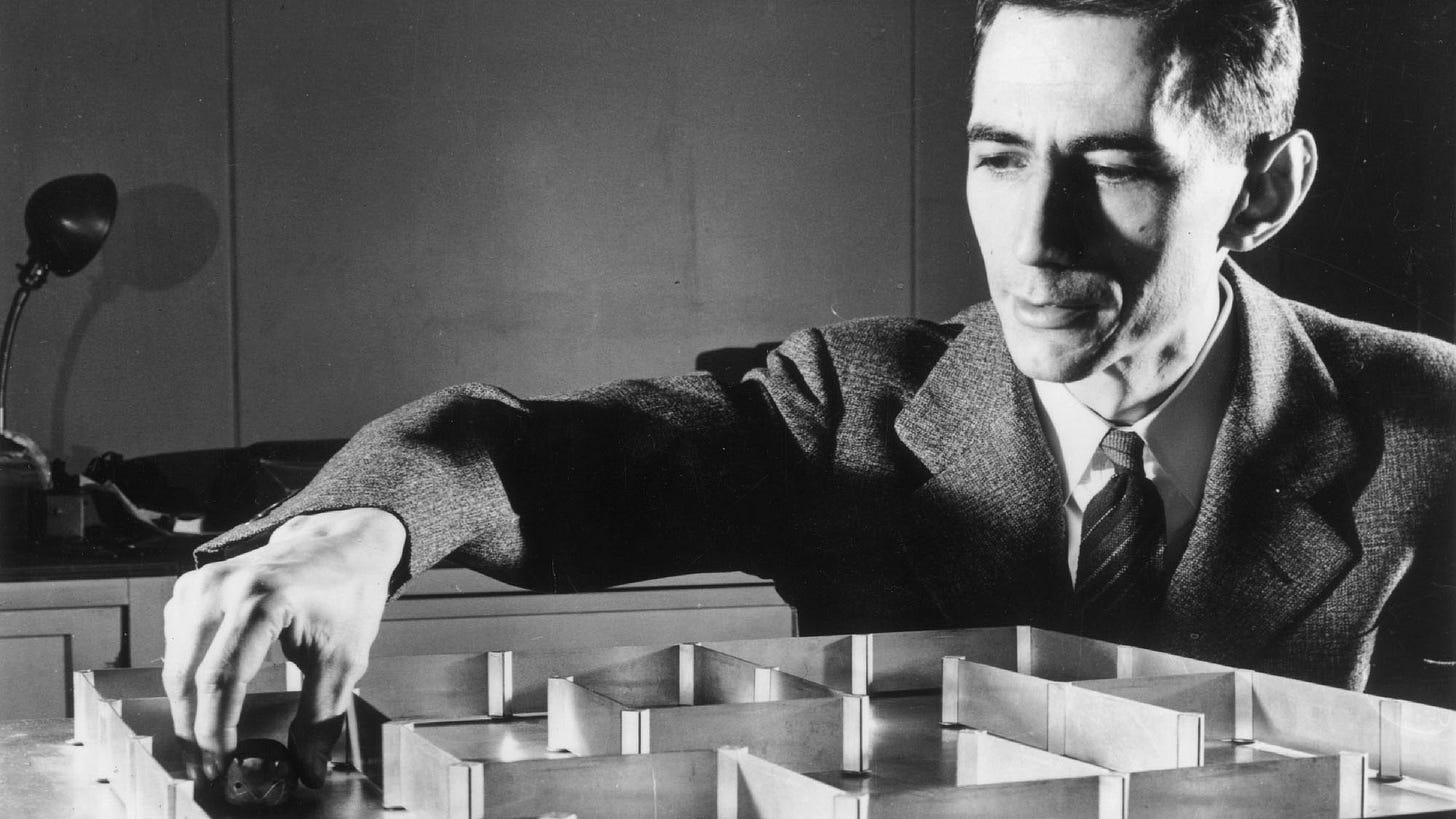

Yeah, it all comes back to a book. So, the origin story and the backstory. A friend of mine had gifted me this great book called The Idea Factory by Jon Gertner. Jon's become a friend, and this book that he wrote was all about Bell Labs. And Bell Labs, in the 20th century, the way I like to describe it is if you look at the early and mid 20th century and you were to combine Apple, Google, and Facebook in one super company that is Bell Labs, right? Circa the '30s, '40s, and '50s. And in The Idea Factory, one of the things that Jon does really well is he paints all these character sketches of the people that were there and what the place was like. And one of the characters is Dr. Claude Shannon.

And you read about this guy and you're like, he's juggling and he's playing chess and he's kind of slacking off on the job, but he is also inventing information theory, which is essentially the modern foundation for everything. It's the reason we can do this. It's the reason we can have this chat over Zoom. And I do what I always... When I find a character I'm interested in, I go on Amazon, type in their name in the search bar, and I see what's out there. And there were a couple of books where he was one of the figures. There's a book called The Information by James Gleick that's great. There was a book Fortune's Formula by William Poundstone, which is more about his life as a gambler and some of the roulette stuff, some of the card playing.

Liberty:

With Ed Thorp.

Jimmy Soni:

With Ed. But no one had done the end-to-end bio. It was like this really... All of my books, I think, are actually when I just see a space on a bookshelf and I'm like, how come nobody did this? This is insane. Right? And so I started just kicking the tires on it, learning more, Wikipedia level research. I didn't go into the archives then. I went into the archives later, but not then. And I just became convinced. I said, someone has to do... The ideas are really sometimes very complex, but the life is so interesting. You should just use that as a Trojan horse to get the ideas through, right? Not to mention, somebody could learn something studying a life. And so that's how the adventure started, was because of a book called The Idea Factory. And then the end result was A Mind at Play.

Liberty:

Awesome. How about you, David?

David Senra:

Same thing. So, I think the process that Jimmy just described is something that I kind of now do for a living, which is books are the original links. And so if you're going to do a history podcast on the history of entrepreneurship and history's greatest entrepreneurs, you're going to have to include Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger in there. And so I went and read every book I could find about Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger, and then I read all of Warren Buffett shareholder letters and I was watching a bunch of the videos that they would do at their annual meeting. And the one great thing about both Munger and Buffet is they talk about all of the people that they admire and the books. They're huge biography nuts, both of them have read hundreds of biographies. And so the way I discovered Claude Shannon was they start talking about this book. Charlie Munger is like, "Hey, you need to read this book called Fortune's Formula," which is what Jimmy just referenced.

And so you can actually see this if you go back in the archive of Founders podcast, it's like, "Oh, David's reading the shareholder letters of Warren Buffet. Then he is reading Poor Charlie's Almanac, then he's reading this book called Jim Clayton First A Dream, which is this guy that started a company. It's actually a mobile home company, and a group of students gave Warren Buffet his biography as a gift. Warren liked the book so much, he bought his company. And then you see he's like, "Oh, then David read Fortune's Formula, then David reads A Man for All Markets, which is Ed Thorp's autobiography. And then he reads The Outsiders because they're obsessed with Henry Singleton." And then that's where I find A Mind at Play because I just said, "Oh, I thought Claude Shannon was a fascinating individual," when I was reading Fortune Formula. And then I told Jimmy this privately a long time ago, when you read the writing, and A Mind at Play is so beautiful, that when you get to the end of the book, you feel...

This is what's really important to me, what Jimmy just handed on as well. It's the ideas might be complex, but the story of a person that was born, that lived, and that died, they did work, they loved people, they had interests, everybody understands that. And so you get to the end of Jimmy's book and you literally have tears in your eyes as he's got Alzheimer's. This beautiful mind. A lot of people use the word genius. With Claude Shannon, he was literally a genius. That was an accurate description of him. And then it just slowly breaks down and you have tears in your eyes when you get to the end of the book because his wife talks about that, his daughter's right there in the end in the chapter, there's this great story that you guys tell where the whole family was... Claude Shannon was obsessed with juggling and his family would as well. And his grown daughter sitting at his side and he looks at her, he goes, "Oh, are you into juggling?" And you're like, damn. And I have a daughter, I know Jimmy does too, because he talked about it in his fantastic book, The Founders, which is on the history of PayPal, which I highly recommend. I've bought 50 copies by the way.

Jimmy Soni:

Oh, my God, that's amazing.

David Senra:

Yeah. Which you know, because I gave away a bunch on Twitter and I just keep giving them away to everybody else. It's just absolutely fantastic. But I love what you put at the end of that book about your daughter. So, again, I think that's the key here, where it's like, I don't understand. Now I just finished the second reading of A Mind at Play. I reread the highlights from the book all the time. I still have a rough idea of what information theory is, I'm just not smart enough, but I understand him as a person. And there's things about how he approached his work and his life. We were talking about this right before we recorded. It's just the biggest lesson from Claude Shannon is don't be distracted by what the exterior world expects of you. This guy won every award you could possibly win, every honorary degree, and he's just like, sometimes I just want to sit in my basement and build gadgets. I want to ride my unicycle down the street. I want to do math because I'm interested in it. It's follow your natural drift. That's one of the main lessons I took away from his book.

And there's a line, if you guys don't mind if I quote, I have a bunch of highlights saved, but this one... I haven't read the book. Let's see. The last time I read the book before, that was 2019. So, it's been three, almost three, over three years up until I spent the last few days rereading it. And this line stuck out to me. He says, "He was a man immune to scientific fashion and insulated from opinions of all kinds on all subjects, even himself, especially himself. A man of closed doors and long silences who thought his best in bachelor apartments and empty office buildings." And that line is just like, I'm only going to pay attention to what I want to do. It's very hard for us to do as humans because we're obviously very social creatures and we just naturally... We use the word memetic when we were talking before we started recording. It's like we're naturally memetic.

And what I liked about Claude Shannon is he's just like, I don't care about the stuff, the wealth, even though he wound up being really wealthy, which is one of the most interesting parts of the book, of course. Just like, I'm just going to look at the stock market like another puzzle. And then I think it was in Fortune's Formula that they made the point, Barons did a report on the top 1,026 mutual funds, and Shannon did a better performance than 1,025 of them. And it's like, they have these giant staffs, it's him, his wife, and their Apple 2 computer. So, that was my introduction to Claude.

Liberty:

Beautiful. Both of you, I second that. And I guess the only thing I could add on my side is being a long-time kind of computer nerd, I kept bumping into Shannon's work but never in great detail. It's always like if you want to understand the digital world, information theory is everywhere in there. But every time you learn about someone, right, about Fineman or Turing or John Von Neumann or all these guys, Shannon is always around somewhere in there. But I never had this clear vision of who he was and what he did until I read Jimmy's book. And then I realized this is the Einstein level genius that's affecting everybody's lives. In physics, without Einstein, nothing makes sense. In this digital world that we're living in, without Shannon, none of that exists or makes sense. And yet you could walk around, ask people on the street and almost nobody knows who he is or what information theory is.

So, that's what I love about Jimmy's book, is it's putting more of a spotlight on a man who totally deserves it. And not only for his work, his theories, but as David says, as a person, he is a good role model to me. Kind of like Fineman's work is great, but Fineman as a person teaches me so much. My oldest son's middle name is Fineman. What I take away from Shannon is the man had an overdeveloped sense of curiosity and play and he found the work fun and valuable in itself. He didn't care about prestige, about all that other stuff. The other stuff comes if you do good work, but that's not the destination for him. For him, it's about the quality of the questions he got to work on, the questions that he asked. And there's a great line in the book about how, with some people, you put one idea in their brains and half an idea comes out. And with people like Shannon, you put one idea in and two ideas come out, or at least two. So, that's the kind of person that I wish I can be. Someone very, very curious who follows what seems most interesting and then tries to generate new ideas and new questions. And that's kind of like a perpetual motion machine in a way. There's always something more that you can look into when you have this kind of mindset.

There's another great line in the book. I have a bunch highlighted here, but we all have our bibles for the Claude Shannon fan club meeting. One line is, "He worked with levity and played with gravity. He never acknowledged the distinction between the two. His genius lay in the quality of the puzzles he set for himself." That's the kind of person I aspire to be. Right? And another amazing thing about Shannon, to me, is he was so early along with Turing and these guys in being like, "Okay, we're going to have machines that will learn, machines that can think." They started thinking about a lot of stuff that we're starting to really live today, that's adding an inflection point right now. And they were thinking about that decades and decades and decades ago. So, I'll stop here with my intro. But yeah, to me, Jimmy's book was the unlock to this person that I always kind of saw out in the distance, out in the fog as I was studying all these cool technical fields, but I don't feel like he got the spotlight that he deserves.

Jimmy Soni:

I think the other... And I appreciate, obviously, all the praise for the book. There's a sort of joke always, it helps to cook with the right ingredients. Part of the reason the book works is because Shannon was this sort of figure. And when going back and rereading it, anytime an author rereads their book, they just cringe throughout. You see all these places, you're like, oh, my god, I would've done such a better job with this, this, this, this, this. But one of the cool things in rereading it is, and this time around, I have a deeper appreciation for all of the paradoxes. And David, you kind of hit on one of the paradoxes, which is he wasn't really out to be a multimillionaire investor who was very successful and yet he became one. He wasn't out to be a famous scientist and yet he became one. He was interested in certain things but could abandon those interests as soon as something else came around.

And yet at the same time, his information theory paper has something like 100,000 citations if you were to go to Google Scholar or whatever. And so you have a person who is hugely complex and paradoxical and because he wasn't out building up Claude Shannon incorporated, he wasn't selling his own brand or getting a really good TikTok channel or whatever, you always wonder, you can peel the service and find all these very peculiar things about him. I like the paradox. The other thing that I remember thinking about in advance of this conversation is he grew up in very humble circumstances, and he was a total product of the Midwest. He was not somebody who was in salons on the east coast, destined for Harvard and then for MIT. His dad was a probate judge and an undertaker and ran a furniture shop, and Shannon grew up basically just tinkering and playing and wasn't one of these people where the ambition was you could burn so brightly, you could feel it.

You always hear these stories of people who, when they'll meet somebody, like Michael Jordan or something, and they're just like, oh, my god, he absolutely wanted to be the best. Or Kobe Bryant's. These apocryphal, not apocryphal, they're probably real stories, but they're sort of told in this way of he was in the gym at 3:00 AM and then he was in the gym at 5:00 AM and then he was in the gym at 7:00 AM. You don't get that vibe with Shannon, and I always really appreciated that because it struck me that it was a far more stable and kind of human success, in some ways. We can't deny that he was successful. He's a long-lasting impact and probably will continue to over the next century, two centuries, but at the same time, you didn't get the sense that he was over weaning in his ambition. There was something really refreshing about that.

I got the sense, I was like, he's the kind of person who actually preferred that he could walk into a grocery store and nobody knew who he was, and if they knew who he was, it was probably because they saw him juggling a few boxes of macaroni or something, not actually for information theory and for being honored by the president and for being one of these scientific greats. I always really liked that. I think I put it in the book, the way I put it is he was a corrective to a lot of the stuff that happens in our era, where big people are expected to operate a certain way and to do this and to tweet and to issue press releases and all that. Shannon, he could barely respond to requests for awards that were being given to him. How badass is that? Somebody wants to give you an award and you're like, eh, if I get around to it.

Liberty:

And another thing is a lot of these super high achievers tend to specialize a lot. Michael Jordan probably only thought about basketball 24/7.

Jimmy Soni:

Well, there was a brief flirtation with baseball, but it didn't go quite as one would hope. David knows a lot about that. I think he did a great series of episodes on that.

David Senra:

Yeah, thanks.

Liberty:

I've heard them too. I think Vannevar Bush... Another one that David did a great episode on, but Vannevar Bush called Shannon a universal genius. Basically, someone that you can point their intellect in almost any direction and they would figure it out. And Bush anchored Shannon to look into genetics for a while. And I think within one year, he was publishing stuff in genetics, something that he knew nothing about going in. I think what he did with every field almost is his super power is abstracting stuff. You take something that used to be a kind of art, very analog, very trial and error, and you kind of learn the recipe over time and you have to always correct it.

Shannon would look at this stuff, be it genes or switches in a machine, and kind of like, what are they really doing? And he would kind of build them as an abstract logic that you can use to create a formula. And that kind of universal genius, that kind of curiosity about anything I think is very rare. I can't think of that many more geniuses that could have made breakthroughs in genetics one year and then turn around and work with the war effort and cryptography and then turn around and help Bell Labs deal with, what was at the time, probably the most complex machine in the world, the communication networks that ran across whole countries and starting to go across oceans. So, this kind of universal genius is very special in itself.

David Senra:

I think what I really appreciate, you guys made the point in the book, where what genius was ignoring the irrelevant, and he got to the heart of the matter. And I think it was in the part where Bush points into genetics, but I think he did this in other domains too, where he can go through the history of the field that he's studying and he just distills down to what is necessary. He might read everything there is, he's like, I picked out what is actually important. And I think one of the biggest keys, okay, that's great for the domain of your profession and your work, but isn't that also a key to having a great life? Understanding it, to get to the end of your life and look back and be like, I really enjoyed the one shot I had at this magical odyssey, this experience that we all call life.

And part of that is ignoring the things that are not important, hacking away at the unessential. And for Shannon, he realizes. Obviously, he became really wealthy. I love that his investment in Teledyne compounded, they said, at like 27% for 25 years or some nonsense like that. And then they're like, "Hey, why'd you invest in Henry Singleton's company?" He's like, "I just had a high opinion of Henry Singleton." But to me, the way, again. When I'm reading these biographies, by the end of the time, I was just having a dinner with a friend who I actually met through the podcast last night and we talked about this, where my goal is if I get to the end of a book on Charlie Munger or Claude Shannon, I want to be able to have an idea in my mind who that person was. So, then when I'm faced with a decision in my life, I can be like, "Hey, Charlie, what would you do in this situation?" Or, "Claude, what would you do in this situation?"

And the idea where you could just hack away at the unessential, I think that's exactly what Claude realized. He's like, "Listen, I'm an introvert, I'm a homebody. Awards are not important to me. Doing more work..." He resisted throughout his entire career other people telling him what to work on. He's like autonomy and control is important to me, building gadgets is important to me. If I have a puzzle, having the freedom to stop and do that. Spending time with my wife is important to me. Spending time with my daughter is important to me. Learning and being around other smart, ambitious people. He talked about Alan Turing he thought was the smartest person he ever met. And that to me is like, oh, the exact same principle he's doing in his work where he is taking all this stuff, all the noise, if you're going to use it in that term, and eliminating the noise. He did that exact same idea for his life and that to me is the main message.

It's like, man, if you want to be like Claude Shannon, you really have to know what's important to you. I was just re-reading. There's a great line, if you guys give me one second, in Ben Franklin. Because Bush talked about the point where... And you guys talked about this in the book too, it's like don't over specialize, right? Ben Franklin didn't specialize. DaVinci didn't specialize. Claude Shannon didn't specialize. So, I was rereading my highlights from Ben Franklin's autobiography the other day. Now keep in mind, that book is what? 250 years old? It's a long time ago. And it said in his autobiography, "Franklin proposed the ideal prayer. And he said the prayer that he thought was ideal for him, it was give me the wisdom that discovers my truest interests." There's no way you can read A Mind at Play and not get to the end and realize that Claude Shannon had the wisdom that discovered his truest interest and then acted on that wisdom. That, to me, is the main lesson.

Jimmy Soni:

There is a great deal of his character that's worth learning from in the ways we're describing, but there's probably nothing more important than the fact that it was very rare for him to look at something, look at a problem or a challenge, and say, "How's this going to look on my resume?" Or, "What are my colleagues at Bell Labs going to think of this?" Or, "What are my bosses going to think of this?" Or, "What are my fellow professors at MIT going to think of this?" I didn't find a single moment where that happened. And it is part of his enduring appeal. And it's useful to think about this, not even at the Shannon level, but just at a personal level. When I was going through school, I can't count the number of times I did something because it would look good on a resume or an application or to advance my career somehow.

But as you get older and more mature, and I think all three of us are parents, as you have kids, you realize how limited that can be. That actually it's a very hard thing to be that utilitarian or instrumental and end up enjoying your life. Shannon also wasn't a buffoon. He didn't put on his sweatpants every day and just hang out and do nothing. He obviously applied to the University of Michigan, became a research assistant at MIT, got his PhD, wrote papers. But in every case, there wasn't this sense of, "Oh, I'm doing this because if it's published in the Bell system technical journal, then I'll get this kind of recognition and then I'll win this award and then I'll win this award and then I can be on TV and then I can..." And David, you've studied more great achievers than anybody, but my sense is that's actually ironically, paradoxically where a lot of the true breakthroughs happen, is when you are pursuing it [inaudible 00:20:37], for its own sake, and you're diving into it and you're like, you know what? Screw it. I don't really care what anybody else thinks.

People who exemplify this, pretty much all children I know before the age of 9 or 10. Then the truth is I watch my daughter play with things, get into things and I can see that she's not thinking about what comes three and four moves ahead. There was something very powerful about that. Shannon had that throughout. You take even a simple example. One of my favorite stories is there was this overgrown tree on his property. So, he lived in this big kind of house in Winchester, Massachusetts and there was this big tree on his property and they had to take it down. And for some reason, they were like, "Okay, we're going to have some people chop it down." He's like, "No, no, no, don't chop it down. Here's what I want you to do. I want you to essentially sand it or file it down, turn it into a wooden flag pole and I'm going to put a Jolly Roger pirate flag at the top, and I want to carve a skull at the very, very top of it." And they were like, "Why?" And he goes, "I think it'd be funny."

That's so epically awesome. How amazing is that? And I don't know. I would wish that I would act that way and I think post having a child, I'm more inclined to do that. But I think it's sometimes really hard if you're an ambitious young person to feel like you've got to do everything with some end in mind. What Claude Shannon reminds you is you can also just do it for enjoyment's sake or humor's sake or just discovery's sake. Go out and try to build a chess playing computer and see what happens. In thinking about it, in talking with you guys, it's one of the things I realized. I am drawn to people like the two of you, because you are like Shannon. Both of you guys are in your own ways.

David, you're one of the few people I know whose podcast includes Michael Jordan, Walt Disney, and Elon Musk. It's all subjects you've gone into super deeply. And Liberty, we've talked about this a million times. Yours is one of the only newsletters that's talking about deadwood and running shoes and capital allocation. And so my sense is that we've probably, each in our own ways, had to overcome a little bit of like, well, oh, what are people going to think? What if it's too random? But I think Shannon's a very useful beacon where he's like, "No, no, no. The more random the better. Turn the tree into a skull. Let's see what happens."

Liberty:

The more people I study, the more I realize that there aren't that many lessons. You have to relearn them over and over again. And what you just talked about, Jimmy, is a good example of find something that feels play to you but work to others. So, the reason why Shannon could make so many breakthroughs is that he loved it and he was probably thinking about it 24/7 and someone else who would've been forced to work on the same field, on the same topic that is only for work, only 9:00 to 5:00, punching out and taking a break whenever he could to go talk about something else because it's not that interesting to them, they're never going to put in all of the work that Shannon did, even if they were of equal intelligence to begin with, which would've been extremely hard to find, right? Because Shannon was at the very top.

But if you have both the raw horsepower and then you work on something that you love so much that you're going to do it all the time. That's why when Shannon came out with information theory, it's not one of those things where 15 other people were just about to come out with the same thing and he just was the first and it was a race and everybody was sniffing around the same idea. You hear about this all the time with, oh, calculus or whatever, that was invented in parallel in a bunch of places. But some breakthroughs like Einsteins and Shannon, they were stuck. Even the super smart people at Bell Labs, they were trying to figure out how to work on these types of problems, how to send a message reliably, how to deal with noise. And they were kind of stalling.

And Shannon's breakthrough was really one of a kind type of thing because of this love that he had for what he was working on. There's a line by Vannevar Bush, he said, "It's a matter of deep conviction to me that specialization was the death of genius." And I think that's what we're losing today. There are few generalists, there are a few... And I get it. Everything is getting more and more complex. So, to go at the very bleeding edge of a field, you also need to be super specialized. But I think there was something special there back in the day when someone could be at the leading edge of multiple field at the same time and figure out what's at the intersection of these fields. And I don't know if we'll get that back with some of our tools that are going to augment our puny brains or I don't know what's going on. But that was one of the great qualities of Shannon.

David Senra:

I think what Jimmy was just talking about, which is a main thing that I discover in my work, is that why you do something, why you're doing it matters. There's a great quote from Steve Jobs who we were talking about in detail before we started recording, and it says, "The older I get, the more I'm convinced that motives make so much of the difference." And he's talking about the heroes that he would study. HP, not the HP of today, but the HP when the founders were running, he is like HP's primary goal was to make great products, and our primary goal here at Apple, at the time, is to make the world's best PCs, not be the biggest or richest. And what a lot of people don't understand, is I talk to people, either they want to start a company or in a lot of cases they want to start a podcast. But to them it's like the company or the podcast is a means to an end. It's like I want to start a company to get rich. So, it's a means to an end. I want to start a podcast to sell more of my products. That's a means to an end.

And what I try to tell them is when I read these biographies, they're doing it because they're genuinely interested in it. Steve Jobs talked about his desire to make insanely great products when he was 19 and he talked about it when he was about to die when he was in his 50s. That was the goal, and if you do that and a lot of other things break your way, then you also get wealthy. The example I used at dinner last night, there's no way that when Henry Ford is working full time, six days a week at the Detroit Electric Company or the Edison Electric Company, and working on his version of an internal combustion engine in the kitchen in the backyard at night and on the weekends, would he think that 20 years from now he's going to own 100% of a company that is worth the equivalent of tens of billions of dollars today.

He just had an idea, he was genuinely interested in, "Hey, I think internal combustion engines are a solution to building a car for the everyman." He didn't know how to do that. He was just interested in it and he pursued his own interest the same way that Shannon did. And so this idea of having an inner scorecard, which I came across at around the same time that I read A Mind at Play for the first time because it's in the book Snowball. I just want to read it because it ties to what Jimmy also said about. It's like he wouldn't even go and pick up awards. They talk about in the book where it's like, "Okay, I'll go because my wife is interested in traveling the world." He's like, "I don't give a shit about any of that." And the way I think about this is what I learned from Warren Buffet, is again, it's why you're doing something.

I just read this fantastic book on Rick Rubin, a biography of Rick Rubin. And in the podcast I made on Rick Rubin, I go, "This is the most inner scorecard shit I've ever heard." Because Rick Rubin is doing it because he truly is interested in making music. He wins a Grammy, he does not bother going to the Grammies to pick it up because he's so busy working and he's so interested in his project. I was like, this is the most inner scorecard shit. He's like, I win a Grammy, I don't even show up. Think about it. Many people in his domain, going back to Jimmy's point, is like they're doing it for adulation, for status, for prestige, whatever the case is. And Rick's like, I'm just doing it for the love of music. Shannon did it for the love of puzzles and curiosity.

But what Warren Buffet said, if you don't mind if I read this real quick, he's like, "It really helps if you could be satisfied with an inner scorecard." And he goes, "I always say, would you rather be the world's greatest lover but have everyone think that you're the world's worst lover? Or would you rather be the world's worst lover but have everyone think that you're the world's greatest lover?" Now, that's an interesting question. Here's another one. If the world couldn't see your results, would you rather be thought of as the world's greatest investor but in reality have the world's worst record? So, that's outer scorecard, right? Because he's going to compare that his mom was an outer scorecard person. All her decisions were made through the lens of what will other people think? It is impossible to have a happy and contented life if you make decisions that way.

And Warren Buffet's hero, in addition to Ben Graham, was his father. Because he's like, my father had an inner scorecard. He just did what he thought was interesting and what he thought was right. And so he goes, "Or would you rather be thought of as the world's worst investor but you were actually the best?" That's inner scorecard. And he goes, "In teaching your kids, I think the lesson they're learning at a very, very early age is what their parents put an emphasis on." So, he's saying, my mom did the outer scorecard, I looked at a very unhappy lady. I was like, I got to do the opposite, and I realized, oh, my dad is actually happy. Let me do what he's doing. And he goes, "If all the emphasis is on what the world is going to think about you..." Imagine Claude Shannon for a second being, "Oh, I can't work of this. What will the world think about me?"

You guys are laughing. No one could see this because it's so absurd. If you read the book, there's just no way that ever entered his mind. And I think that's a trait I'm trying to emulate. So, then he goes, "My dad, he was 100% inner scorecard guy. He was really a maverick, but he wasn't a maverick for the sake of being a maverick." Claude Shannon. Maverick, right? But he's not a maverick for the sake of maverick, he's just being who he is. He just didn't care what other people thought. "My dad taught me how life should be lived."

Jimmy Soni:

Wow. The other part of that, there's sort of two other things that emerged from this and I'm glad we're doing this in the way we are, which is free form, there's no real plan. Shannon would be proud. There's two other things that emerged from what David said that they came to mind for me. One is, and all three of us have lived this in our own ways, the power of the side hustle. Information theory was now what Claude Shannon was being paid to do at Bell Laboratories. It was what he was doing on nights and weekends. And he did it for 10 years. So, it was a 10 year epic side hustle. And it was one of my biggest takeaways from the book and in doing the research. I was thinking to myself, so much of what we acknowledge him for is not the stuff that paid the bills. What paid the bills early on in his life was the research assistantship at MIT, then he got a fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study, then he got that job at Bell Labs.

But we know some of that work, but not really. It kind of formed some of the foundation for the later efforts. But a lot of the things that, for example, his chess playing computer that's in a museum now, he just did that on the side with his wife. He took this mouse, this artificially intelligent mouse that he built called Theseus, took it on a nationwide tour. Bell Labs was so happy about it, Bell Labs didn't tell him to build it. He and his wife were just tinkering in their garage and built this thing, and it turned out to be very cool and people really liked it. But I think one of the things that we do is we underrate the side hustle. Actually, all my books are side hustles. A lot of the coolest things I get into are just side hustles. But if you take your side hustles seriously, like Henry Ford, you could end up, like you said, owning 100% of a company that changes the automobile.

I think that's one key lesson for me from Shannon is, man, embrace the side hustle but take it somewhat seriously. Have some discipline around it. Not in a kind of breaking your back way, but in a don't abandon it at the first moment of difficulty, because he faced a lot of difficulties trying to figure out information theory. The second thing I think is he had this quality of combining what I think we wrote in the book was combining head work with hand work. And so he had a physicality to his work that I think sometimes we digital people forget about. I forget about it all the time. But there's something really powerful in the fact that he didn't just write papers and then publish them in journals. He did that and built a machine to solve a Rubik's cube or built a flame-throwing trumpet or built a rocket-powered Frisbee or any of this stuff. And I think that's very cool.

Liberty:

The box that when you press the button, it opens up, there's a hand that comes out that presses the button again, which closes the box, right? That's the kind of stuff you do because it's cool, but you never know when something you start working on because it's cool becomes something bigger. If you knew in advance what you were doing, you wouldn't call it research. Reading the book, I had a question for you, Jimmy. I'm curious what you think of this. There's always a lot of focus put on the genius as a person. But I think it's Brian Eno that came out with the concept of a scenius. It's kind of a scene that brings out the genius as a group. And so reading about Shannon, he's around Alan Turing and John Von Neumann. He meets Einstein, he's at Bell Labs with a bunch of people who are inventing the fax machine and solar cells and working on radar and sonar and cryptography and they invented the transistor there. Do you think that's the scenius where if you put Claude Shannon somewhere out there in Antarctica by himself, he'd be brilliant. But was he kind of super charged by the people around him? Or it's probably impossible to know, but I'm curious what you think about that aspect of it.

Jimmy Soni:

Oh, I think there's no denying that Bell Labs was the perfect place for him to work. I would say Bell Labs as a scenius is an amazing thing to study. But it's also, if you take Shannon out of Bell Labs, you don't get Shannon, for a few reasons. One, no other employer would've allowed their employee to unicycle down the hallway and take long lunches and breaks and play chess all day and whatever. That's the obvious thing. But then the not obvious thing is you end up in a situation where he's given freedom, but he has colleagues around who are doing interesting things. He has colleagues around who he can bounce ideas off of, and he is, broadly speaking, working on problems in telephony, in the war, in making missiles hit their targets better. So, he is sort of being challenged with the kinds of problems that are going to engage a part of his mind that leads to information theory.

But I don't think there's any doubt that it mattered a great deal that he had people like Von Neumann around, that he had Vannevar Bush around earlier in his career. And then at Bell Labs, he has the founders of the transistor, and all these other people who are really important. And then obviously his friendship with Alan Turing. I'm a believer in the scenius idea. I wrote about it and The Founders, obviously the PayPal mafia kind of fits this motif. I think one of the cool things with the internet is my scenius can be geographically promiscuous. I'm friends with you guys and it's entirely possible 30 years earlier we never would've known about each other. But we have so many crosscutting, overlapping interests. It's the best thing about the internet, is that your scenius can be this interesting group of people that you're connected with despite not having to live or work in the same place. Shannon didn't have that. Shannon got lucky, lucky and good, that he ended up at Bell Labs. This is the ideal scenius for somebody like him.

Liberty:

That's the ultimate history question. It's always you can wonder how many other geniuses were alive at the same time and they just never got to the right scenius, they never got to the right place, they never got connected to the right people to work on the right problems. Or go back 500 years. Einstein is born and he's farming all day long or something. That's the thing with the internet, is how much of humanity's potential is being unlocked just by having the opportunity to find your people, find your problems, find the right information to be the fuel for your problems.

David Senra:

Scenius is a very real thing that I found a lot in my work. In fact, I'm doing this three part series on Paul Graham, the last one's coming out today. In this one, he talks about the importance of that. Let me read from his book Hackers or Painters real quick, because it came to mind as you guys were talking. And he's talking about good design, but good work. He's like, "It happens in chunks. Something was happening in Florence in the 15th century and it can't have been genetic because it isn't happening now." And these next two lines really I think was speaking to what Jimmy was just talking about with Shannon. "Nothing is more powerful than a community of talented people working on related problems." What was Bell Labs? That's exactly what that is. And then Paul says, "Great work still comes disproportionately from a few hotspots."

And when I read that in Paul Graham's book, I'm like, oh, I've come across this a million times. The thing that always pops to my mind is like Enzo Ferrari. Enzo Ferrari dedicated his life. He's one of the history's greatest successes. He worked on Ferrari the company seven days a week, 12 to 16 hours a day for 60 years. Completely obsessed with that. And he goes, "It is my opinion that there are innate gifts that are a peculiarity of certain regions and that, transferred into industry, these propensities may, at time, acquire an exceptional importance." And then he applies this to his own work. In Modena where he built his works, "In Modena where I was born and set up my own works, my own factory," listen to the words he uses, "There is a species of psychosis for racing cars."

Jimmy Soni:

Wow.

David Senra:

He is literally saying, "I could not have done what I did with Ferrari if I wasn't born and raised here around other people that shared my psychosis for racing cars." Scenius is a very real thing. And I love what you said because I do think, for the first time in human history, it may be decoupled from geography. I do think geography and being in person still plays a role. But like you said, right now, we're thousands of miles apart and yet we can sit here and have a meeting and really share ideas about the same stuff. And then more important, when this is over, think something's going to hit you that somebody said a week from now. Like, oh, wow, that applies to this other idea I have. And then you go and talk to other people and it kind of just spreads from there. But I'm very into that idea.

Liberty:

As you were speaking, I know how in love you are with the medium of podcasting, David. And I was thinking how maybe the scenius is becoming more fluid as far as geography, but how about time? So, someone could be listening to a podcast from five years ago or anytime. Books are kind of like that. You can read very old books, you can read books from dead people, and have kind of telepathy with them. One way telepathy where you're inside their heads. But we are building new mediums that make that even more powerful, that create new ways of finding ideas and people across both geography and time. That's super interesting. We're seeing it. The Manhattan Project, the Apollo Project, all these were kind of manmade sceniuses. Silicon Valley today. Is it random that all these companies and all these startups all start in the same place? I think there's a huge network effect to being close. But over time, there's probably a move in the more dispersed direction. It'll be very interesting to see over time how many great founders and great things are started in places that we would never have expected. Someone in Pakistan may be the next billion dollar one person company someday or-

Jimmy Soni:

I think the other part of it that's important from the Bell Labs perspective and just in general is it's not just time spent working, it's also time spent socializing. And so this is where my thesis about digital sceniuses may fall apart and that's fine. But it is the case that part of what I've seen Paul Graham write about in the past but just heard anecdotally about Silicon Valley and then also read about at Bell Labs and saw play out in Shannon's life, is this idea that it's not even that Shannon was talking to Bill Shockley about information theory. It was that they would play chess together or have coffee together. There were these informal kind of bumping into type of circumstances and time spent doing anything other than work that was generative, that was creative. I think that's a big part of the scenius.

So, even within the PayPal story, there was a lot of time PayPal spent been playing video games, guys. It was a big gaming culture. And I think that's additive to the success and multiplicative for the success. It doesn't take away from it. To me, that's a big part of it. It builds these bonds of trust. You build bonds of just liking to be around certain kinds of people and then you know when they're on, they can do certain things. I don't think that carries over maybe as well to sports, though I would sort of defer to David on that. But my sense with Shannon is it was the chess playing, playing go, having tea, the Bell Labs culture, not so much like, "Hey, let's work together on this problem and this is how we're going to do this thing." That happened, but it was really the other stuff that made the scenius what it was.

Liberty:

Yeah. How many time in the book is the cafeteria mentioned, right? That's where Alan Turing and Shannon were meeting. And they couldn't talk about the war stuff because it was classified. And I so wish to see the alternate history where they could have talked about it. And maybe nothing special would've come out of it. Maybe huge breakthroughs. But what you said made me think about, it's exactly why, when Steve Jobs designed the Pixar offices, he made them in a way that people would have to meet and there would be all these common areas and places where people would intermix. And I think you tried to do the same thing with the new Apple campus. But all these unstructured interactions are where new ideas come from. And what I'm hearing is you're saying we should do more calls without an agenda, just talking random stuff.

Jimmy Soni:

Pretty much. I mean, that would be super fun. The other part of Shannon that is interesting, and it's hard to... There's a group of people who criticize Shannon for the later part of his career not being as successful as the first part. So, he sort of publishes information theory and then gets off the stage. And I've always been on the side of, I actually disagree. Because if you look at the number of inventions he made at the tail end of his life, if you look at the various things that he was engaged on, the stock market, gambling, wearable computers, different kinds of just calculating devices, he's phenomenally productive. It's not productivity that's necessarily appreciated in the same way. But that's the one place where I'm like, oh, there's a little bit of criticism even from some fellow scientists. They were like, "Well, you could have done so much more Shannon, you could have gone to MIT and built that department into something."

And I'm thinking to myself, that's not at all what he was about. He was ready to just move on to other things as soon as they presented themselves. He felt like he had said everything he needed to say in that field. And it turned out he was proven right just 50 years later. There's something about that though that there was always people who are suspicious or critical of people who do pivot or go to a different direction. And I think it becomes really dangerous because then it makes it harder for people to do exactly that. It makes it actually harder to be Shannon.

Liberty:

Yeah. So, many great scientists, after they win a Nobel prize, they become a lot less productive because now they're a Nobel prize winning scientist, so they have to work on serious stuff and they have to spend all their times in conferences, and it restricts their freedom in lots of ways. And I think that's probably one of the reasons why Shannon wasn't interested in all that stuff. He just saw it changing his life in the ways that made it worse, not better.

David Senra:

But it's all outer scorecard stuff. Okay, you don't get to decide what I work on. You think somebody should work on that? Go, what are you doing? You go do it. This ties into my absolute favorite... You never know when you read a book, and this is why it's my favorite medium ever, because you could read 600 pages and there'll just be a line or sentence that just sticks out in your mind and that you'll never forget. You guys mentioned Michael Jordan a few times. I read a 600 page biography on him. I have probably a hundred highlights in the books, but that one line where he's talking about going to the dream team and wanting to see how other people at the top of his profession, what their practice habits were. And he says, he realized he just put so much more emphasis on practice than these other people did, and he says they were deceiving themselves on what the game required. That's one line that just grabbed a hold of me and never let me go.

The line in this book that grabbed a hold of me and never let me go and that I've reread probably, I don't know, 50 times in the last three years or four years since I read the book, is he never argued his ideas. If people didn't believe them, he ignored those people. Yeah, it's not my job to convince you. I'm not trying to convince you. I'm sharing ideas. If you find the ideas valuable and you want to use them, great. But we're not going to get into some kind of debate here. What you do is irrelevant to me. I love the thinking of Naval Ravikant a lot. My friend Eric Jorgenson wrote this fantastic book called The Almanack Of Naval, which second to Jimmy's Founders is the book that I've given away the most, bought the most copies of.

And Naval says in that book that the reality of life is a single player game. You're born alone, you're going to die alone, all of your interpretations are alone, all of your memories are alone. You're gone in three generations and nobody cares. Before you showed up, nobody cared. It is all single player. And I feel that Claude, he understood that. He might not use those words, but he played life on the mode that it is. It's a single player. It's like, I get to decide how I spend my time and what's important to me. That doesn't mean you go around abusing other people or being selfish. Obviously, you're married, you have kids, you have to compromise on some level. But that's the biggest thing that I take away from Claude. It's just think about Ben Franklin's prayer. Really take time to discover who the hell I am as a person, what am I actually interested in? Not what other people tell me I should be interested in.

I had a very depressing moment that happened recently. I'm not going to say who it is, but there was this founder who was well known, winds up selling his company and you hadn't heard from in a while, and I just happened to see something he wrote. And essentially, to me, he made the fatal mistake of selling your best idea. And then he talks about, "Hey, I'm doing some research on what my next thing is going to be." And then out of his mouth comes all of this jargon. It's like I'm looking at web three, AI, all the shit. Essentially, here's a list of seven trends, seven ideas I did not come up with, but other people talk about. So, therefore, I must have to go work on.

And I'm like, what? Fuck the trends. What's important to you? You're going to spend half of your waking hours working. You cannot let other people decide what you work on. And so you go back to that line where it's like he never argued his ideas. It also says there's another great line, "He was not someone who would listen to other people about what to work on." The people that do the greatest work. It's just like they're following their natural interests. They cannot explain to you why. The line I use all the time is what Jeff Bezos says, that, "Our passions choose us, we don't choose our passions." He's been interested in rockets since he was five years old. Just took him to have to found Amazon and make enough money so he could start a rocket company. When you're five, you're not sitting down like, "You know what, let's have a logical discussion about what I want to work on." You're just interested in the stuff you're interested in.

I started reading around that same age. No one told me, "David, books are a really good resource and you should spend a lot of time reading." I was just compelled to read. And so again, the actual life story, the person behind this book... And this is something I get to do all the time where you get to the end of the book and you close... You know what, I'm going to read you what I wrote on the last page of your book. I wrote this yesterday. Because this is something I get to experience all the time where not only is the book over, but most of the people I study are dead. Not only is the book over, but their life is over. And so I get to the point, he does this hilarious thing where he had decided what he wanted his funeral to be, and it was this massive parade, and it winds up not happening unfortunately. But it just, again, speaks to him as an individual. And that's why I feel like you get to know who he is at the end.

And so the book ends and he passes away and it talks about where he was buried and everything else. And I wrote this, I go, "We all share this fate." And the lesson here is like, let's not waste a day. At one point, all three of us and everybody listening to this, you are going to take your last fucking breath. And are you going to get to the end, worried about... When you're on your deathbed. I promise you, you're not going to be worried about, oh, you know what? I should have worked on that project that other people, other scientists or other podcasts or other writers told me I should do. You're not going to think that thing. You were like, damn, I fucked up and I'm dying, and I didn't even get to live the life on my terms. Shannon lived life on his terms. Yes, his intellect is extremely rare, but his way of doing life is even rarer.

Liberty:

His friends kind of did the same thing, right? Singleton and Ed Thorp, these people all knew each other. And I don't know if they influenced one another or they just found each other because they were like that. But that's very powerful. It's the stoic thing where imagine you didn't have your eyes, you couldn't see. And then you imagine in great detail what your life would be without your eyes and everything that would be different. And then you remember that you do have your eyes so you can appreciate them. You can do the same exercise with your life. Imagine if you didn't live your life the way you wanted to. If you add this outer scorecard, if you worked on stuff that didn't matter, and then try to realize that you still have the choice right now not to do it. You're not on your deathbed, right? There's always a course correction that can be made, even if in the past you made mistakes. Anyone listening right now, think about this seriously. David is giving you great stuff, great wisdom. This is important.

Jimmy Soni:

The interesting thing about the funeral planning. So, it's buried in the archives at the Library of Congress and we tucked it into the tail end of the chapter where he passed away. And if you read this plan, it's utterly hilarious. It's actually he wants seven unicycling pallbearers, a 417 person band. He wants this famous British chess player playing against a computer on a float, a Macy's day parade type float. Oh, he wants multiple people dressed up as chess pieces kind of ambling down the street. It's this epically funny, hilarious thing. And there was a bunch of things I took from it. One was he just had this hilarious sense of humor and he didn't care if he was going to write out his own funeral plan. The reason that I mentioned it is because his family actually kind of cringes when they think about it, because this is their father's passing away, but he thought it should be this hilarious epic celebration that was really funny and honored all these different interests that he had. And he didn't care that if he wrote it down, somebody would find it later, he might be mildly embarrassed. Who cares? I thought that was really cool.

And then the other interesting thing is, in a way, it's one of these odd things that, even at the tail end of his life, when the Alzheimer's was taking over, people who we interviewed who were around him at that time and spent time with him, including his daughter, he was not gloomy. At one point, somebody we interviewed said there was this period where he was using a walker. He had become physically debilitated after breaking his hip. And what he did was he started taking it apart to see how it worked and see if he could make it better. So, he was who he was to the end and didn't really care. He wasn't going to go build a better walker company or he wasn't going to write a paper on it. He just was actually a tinkerer and was like, I'm going to take this thing apart and see how it operates.

And there's so much of that that I would hope for myself and that I hope I have enough, call it Moxi, right? Or courage to say, "I don't really care what those others think. I'm not going to do that. That's just not for me. I'm going to focus on the things that give me joy and that I have some sort of appreciation that I'm good at them, but they're more inner scorecard than outer." And I think it is hard to do, but it's the reason that I think the book was so inspiring to work on over time. I was just trying to tell the story, but you walk away and you're like, whoa, this person lived life so differently from people who are of comparable intellect, and we all sort of need a dose of it. It'd be really useful because I think we'd all walk around a lot happier.

David Senra:

And in the world that we tend to... You just wrote a book on it, obviously. Startup culture, right? Liberty's very interesting in investing. I run a podcast on the history of entrepreneurship. In this world, something that is chased erroneously in many cases is some people are doing the work for the sake they have to bring this product into the world. That book, like you said, it's like I'm looking at a bookshelf, it's missing, I have to go fix that problem. Claude Shannon needs to be on the goddamn bookshelf and I'm going to put them there. No one else is going to do it. I'm going to go do it. And what I think a lot of people get distracted in, and I'm knee deep in this right now because I've spent the last three weeks in the mind of Paul Graham, which is really, really fascinating. I read his book, which is a collection of websites, and I read all the essays that are available for free on his website. And he talks about this all the time.

This is a guy, not only did he experience this himself because he sold a startup, but then he started Y Combinator, which then he's seen, he's funded literally thousands. He's talked to thousands of entrepreneurs. He's seen, almost like he's watching a game tape over and over again. Which is the way I think of if you read a bunch of biographies, you're watching game tape, which is somebody else's life play out. And so then you can derive lessons from that game tape and from those examples. And what Paul says is first he makes the point that how many people actually get to work on things they actually truly love. He's like, out of billions of people who have ever existed, a few 100,000. And he goes, the reason that you're not going to do this, and the reason it's likely you're going to fail at this very important thing in life, which is finding work that you love to do, is because you're going to be distracted by prestige and by money.

You're not going to listen to what's inside your own heart because prestige is just the expectation of the external world and money. And so I was having this conversation last night too. It's either we have the ability to learn from the examples of other people or we do not. And a lot of people don't. They'll read the books, they'll understand, but they're like, I still have to find out for myself. And one thing that's very common is when you're doing something you don't want to do and you're only doing it for money, you're going to get the money and you're going to wonder why you're not satisfied. That example that I just talked about is... I could point you to hundreds of examples of people doing that. And so what I'm saying is, if I fail to learn from the experiences of other people, then that means my entire life's work, which is Founders podcast, is useless.

And so that is just something that I constantly remind myself is, listen, I'm going to stay focused on what I'm really passionate about, what I like to do. Chances are there's probably millions of people just like me with that have same interest. Over time, I will reach those people and then I'll get all the economic rewards that I deserve. But if I allow myself to be pulled in other directions and just do things for money, then that means I'm not learning from the examples of people that did that and then say, "Hey, that's a bad idea. Don't do that." And Shannon was completely closed offset. There was nothing in his life story where it was like, "Oh, you know what? I could work on this interesting math problem. I could work on this theorem. I could build a gadget." How many people wanted him to do lectures? And he was terrified. He did that MIT lecture when he was talking about his method of investing when they sell out and they have to move to a bigger arena, or not arena. A bigger form. But after that, he is just like, I feel I have nothing unique.

He could have made a ton of money like a lot of these famous scientists do. He just goes around, he writes books, kind of trades on his fame. He's like, eh, I'm not going to do that. And so again, another example there, it's like after you're already able to have a certain level of wealth, I'm not talking about being completely broke, not being able to pay the bills, you got to do things for money. But a lot of people, where they make the mistake, and we mentioned Ed Thorp, which he's really the one that crystallized this idea for me, where after he's already made the money he needs to make, he's like, I'm not going to go and trade more of my precious and limited time to make more money. I'll never spend all the money I already have anyways. I'm just going to go spend more time with my wife. I'm going to go spend time with my son. I'm going to go build a wearable computer. I'm going to write a book or whatever I'm going to do. And again, I think that's a key thing. It's like, do you have the ability to learn from the experience of other people? And if you do so, it just makes your life a lot easier because you get the insight without all the pain.

Liberty:

I'd like to go a little bit into the technical stuff that Shannon worked on, just to make the listener curious. If you're listening to my voice right now and then you haven't read the book, you can hit pause and go on Amazon or Jimmy's site and order the book. That's very important. And then when you come back, I just want to explain a little bit how much Shannon changed the world. And I'm not going to get all of this right because this is not my expertise. But the analog computers that Shannon was working out with Vannevar Bush before all these revolutions, if you wanted to figure out something very complex, a very complex problem about the atom or a star or something, you would kind of custom build a computer that was as big as a room, could weigh a hundred tons, and you would put these things together that would be an analog to what's going on in the thing that you're studying.

So, your computer would be kind of like a giant atom or a miniature star. These are lines from the book. You had to reproduce an analog of the things that you were studying and then the computer would spin around for hours and days and sometimes would break and you'd need students around 24/7 to maintain it. And that was the state of the art for solving problems with a machine back then. And what Shannon was able to do was realize that everything in logic, all of the billion things like the true or false, if, or, but, all these things could be represented by switches. And basically, what we have now, transistors are very, very simple switches, but if you put enough of them in a row, you can produce any kind of logic. This kind of leap forward, they were hitting a wall with these analog computers, these analog machines, and humanity needed to change branch and go in this digital direction because we were hitting a wall.

Everything in the modern world today would not be possible without Shannon's breakthrough. The other big thing was that, at the time, every message was kind of like its own thing. If you're sending a telegram or you're sending a letter or you're recording audio on a vinyl, all that, every format is very, very different. You could not abstract them to be all of the same thing, but that's kind of what Shannon did, right? After Shannon, the medium didn't matter, the message didn't matter, the sender, the receiver, all these things that matter, you don't have to understand what it is, what it's about. You could abstract it all to a series of bits. And they came up with the term bit at the cafeteria. He asked some of his colleagues for a name for digital units and someone came up with bit. This abstraction, this taking all these things that used to be different, that used to be studied separately and making them all of the same thing so that you could do a lot more with it, that's just brilliant. That's the Einstein level breakthrough.

And then at the time, before you had this, you were always dealing with noise. You have a radio station, you're sending a message across the Atlantic and a super long cable, and the farther away something else is, the more noise you have. And so you're cranking up the power to try to get through, but then you're also amplifying the noise or you're frying your wires. That was also hitting a wall. And so what Shannon did was allow this information to provably be sent and received without error. If you know what your medium is, you know how much noise there is, you can add redundancy and later you have checks, sums and all kinds of stuff. But the basic principle of you can mathematically prove that, with this much noise, you had this much redundancy, and you can be certain that on the other side, the person is getting the message that you sent instead of something garbled or something different. That kind of stuff, how useful is it today? Everything runs on these principles. So, that's just kind of like a teaser. To get all the details, you have to read at the book. But that stuff is everybody should learn in school why the world is the way it is today, and Claude Shannon should feature heavily in that.

Jimmy Soni:

Obviously, I couldn't agree more. And I think the one thing I want to say as we're kind of closing out is don't let the ideas and some of the ideas around Shannon, information theory, and around error correcting codes and redundancy in entropy and compression algorithms, don't let that sort of intimidate you. I am not an electrical engineer. I wrote the book as a non-expert and that was actually a huge asset because I didn't know anything and I had to have people explain it to me in layman's terms. And so the book hopefully does a decent enough job of that. But the other place, if you're sort of have some allergic reaction, is start with The Bit Player, which is this documentary that was done by Mark Levinson who did a documentary called Particle Fever, which was all about, I think, the Higgs boson, the God particle, his follow up act was about Claude Shannon and The Bit Player is fantastic.

He found footage, never before seen footage of Shannon unicycling. He does a really good job of explaining what information theory is, why it operates the way it does, and again, does it in easy to digest. You just sit back, watch, and you'll kind of understand what Shannon's life was about and also understand what his work was about. And so I don't want anybody to be kind of intimidated. Plenty of people have read about Einstein without understanding the theory of general relativity. And so in a similar way, I don't want to make Shannon... Part of the reason I wrote the book is because I thought the life was a way in. It's a book where you can enjoy the life and you don't need to be any kind of electrical engineer to make heads or tails of it.

David Senra:

There's a powerful idea behind what you're saying and something I repeat over and over again. It's don't copy the what, copy the how. There's a bunch of people that I've read several books on. Claude Shannon, Dee Hock which is the founder of Visa. We've mentioned him a couple times, Vannevar Bush. I don't know how they did what they did. For Vannevar Bush, it doesn't even make sense how one person accomplished this much in a lifetime. And he's like history's Forrest Gump. He's at every single important part of so many important... Especially in American history and then world history when you think about the role he played in World War II, it's like this guy's just popping up everywhere. But I think what you said is dead on. Is I'm never going to understand the nuts and bolts of information theory. I'm not going to understand everything that was in Vannevar Bush's brain and linking together science and engineering and government and private industry and helping all those things work towards a common goal, which is defeating the Nazis, right?

I'm not going to understand really how Dee Hock, it was even possible that he started Visa for where it spawned from. But I can understand, very similar to what Claude Shannon does where he looks at everything. He's like, it's not what's right in front of his face. He's looking at the meaning behind it. And they use the word abstraction over and over again in the book. He takes the idea and turns into an abstraction, and then essentially he pulls it out of wherever it is and then you can use it for other different domains. And so the way my very simple brain compared to Claude Shannon's brain works is like, oh, I'm not copying the what, I'm copying the how. And for the Shannon thing, I think one of the most important things that I haven't mentioned that I wrote down is just the value of just following your curiosity. And it says, I think the history of science, I think this is a direct quote from Shannon, if I'm not mistaken. He says, "I think the history of science has shown that valuable consequences often proliferate from simple curiosity."

Now, where the curiosity that the three of us have and where it's going to lead us in the future is not going to be the same place where Shannon's curiosity led him. But you can use that idea. It's like, I'm not copying what he applied that curiosity, I just want to apply the fact that he did, the how. Its like, okay, when I'm alone with my own thoughts, what am I actually interested in? Not when I'm going and checking, its like, oh, everybody else says I should work on X, Y and Z. It's like, oh, I'm just curious about this. Let's just go see where that leads. I mean, think about it. My curiosity led me to Claude Shannon. It led me multiple years here to be on a Zoom with the author of the book. That's fucking crazy. That universe is crazy. It just started from, "Hey, I thought Warren Buffet is kind of an interesting dude, seems to know a lot of shit. Let me read his shareholder letters. Let me hear him speak." And then that just led to one thing and led to another thing. And I just followed my natural curiosity. And here I am now, three or four years later, doing this podcast with you.

Liberty:

Yep. I got to read straight from the book, from the good book, page 218, 219 in the hard back. I think that's the two pages where I have the most highlights. And when you said you have to copy the how, right? How he did things, even if-

David Senra:

Don't copy the what, copy the how.

Liberty:

Yeah, exactly. What I'm doing is nothing like what Claude Shannon is saying, but when I read the way he approached problems, right? I'm just going to read a few sentences, right? "Great insights don't sprint from curiosity alone, but from dissatisfaction. Not the depressive kind of dissatisfaction, but rather a constructive dissatisfaction. A genius is simply someone who is usefully irritated. For Shannon, there was no substitute for the pleasure of seeing that results. He was doing it for fun and to scratch his own itch." After that, how does he solve problems? Simplifying. If you can bring the problem down into the main issues, you can see more clearly what you're trying to do. You have to ask yourself the right questions, and then if that doesn't work, he talks about encircling the problems with similar questions that are not quite what you're trying to solve, but similar question that may be solvable. Or maybe you break down the big question into smaller questions that you can approach one at a time and make some progress there.

Restate the questions in different way. Don't become trapped by sunk costs. If you've put a lot of work in a certain direction and it's not working, you should be able to cut that and move in another direction. He is basically giving you a blueprint to how he's thinking about solving things. And that stuff applies whether you're a florist or a founder or a coder or a scientist or whatever. This kind of thinking is extremely valuable, and I don't think enough people are taught how to solve problem, how to ask questions. We're so focused on answers, right? School is all about getting the right answer. But if there's one thing I've learned from Fineman is that having all the right answers without understanding, without knowing how to ask the right questions, it's not going to lead you anywhere very productive.

David Senra:

Love it.

Jimmy Soni:

I love it.

David Senra:

Thanks for inviting me on, guys. This was fantastic.

Liberty:

Thank you for coming. It was amazing. The very first official Claude Shannon fan club meeting. I think that was a good one. I think hopefully everybody listening to this is going to buy a book. Jimmy and I are going to do a giveaway, so we're going to send you a bunch of free copies.

Jimmy Soni:

Signed too.

Liberty:

Signed too, right? So, you can have a second copy. You can buy your own copy, get a signed one, and then give away the first one to a friend. Christmas is coming.

Jimmy Soni:

And I think we're going to even potentially, the three of us, try to put together a screening of The Bit Player sometime in 2023. I think it'll be fun, expose people in a different genre. And I would just say this is for fans of Liberty and fans of David, and I count myself lucky to be in both camps, to me, you guys live this ethos, live Shannon's values almost more than anybody I know. The sheer range of your interests actually is something that other people listening should emulate. It is. It's amazing the degree to which you guys just dive in, find a topic, and are like, "I'm going to go whole hog. Who knows where it goes. Who knows where spending three weeks with Paul Graham's mind goes, but let's see where it goes. Who knows where obsessing over deadwood and writing about it goes, but let's see where it goes." And I think, Liberty, you're now in touch with the author of a book about it or something. But I thank you for having me on, but also just thank you for doing that thing because that is actually the thing that leads me to my book projects. And sometimes I think I'm crazy. And so now I'm like, no, no, no. I'm appropriately sane. If I'm with Liberty and David, this is perfectly acceptable behavior.

David Senra:

I feel the same way about you. Your book on The Founders is absolutely amazing. The fact that you spent more time researching it than PayPal existed before the acquisition, it just speaks to... I don't know, I feel like the reason I bought so many copies, the reason I recommend it to so many people is because I know how much work you put into it and it's like your life is going to be better. It is worth the week that it takes to read the book. And you're going to find ideas in there that you can use and you might not use them right now, you'll use them in the future. So, I feel the same way about you. It's incredibly impressive. And then the idea that you've done this now, I know you wrote another book too. But the idea you did this also with Claude Shannon is just absolutely amazing.

Liberty:

I second all that and I have to say that we don't do fan club meetings about just any book, right? This is a special book.

David Senra:

Honestly, I think if you guys are cool with it, I think we should do it for The Founders book too.

Liberty:

That's a great idea.

David Senra:

Because I got a ton of notes.

Jimmy Soni:

Yeah, I'd love to.

David Senra:

Yeah, 100%.

Liberty:

Let's do it.

David Senra:

Yeah, absolutely.

Liberty:

And I'll leave you with a line I like. I don't remember who said it, but it's curiosity is contagious. Pass it on.

David Senra:

Love it.

Jimmy Soni:

That's great.

David Senra:

All right, guys. Thanks for having me on, Liberty. Appreciate it. Thanks.

Jimmy Soni:

Thanks, Liberty.

Liberty:

Have a good day. Bye-Bye.

Wow, you made it all the way down here. 🍪