2️⃣ Mark Nelson is back for Part 2!

(If you missed it, here’s Part 1 🎧)

In another wide-ranging conversation, we discuss the likely energy policy of the new U.S. Administration, particularly focusing on Chris Wright, the incoming Secretary of Energy. 🦅🇺🇸

We explore Wright’s background in the oil and gas industry, his connections to the nuclear sector through his board position at Oklo, and what his appointment might mean for both conventional and advanced nuclear power in America. 🛢️🛢️🛢️⛽️

We also get into the dynamics between different energy sources, including the relationship between nuclear power and electric vehicles, the future of LNG exports, and the complex economics of oil and gas production.

Don’t miss the under-discussed love story (💞) between nuclear and batteries. ☢️🔋

We also touch on recent regulatory challenges facing Big Tech companies’ nuclear power initiatives and how the energy landscape might evolve in the coming years, including how solar power and batteries will likely fit into this puzzle.

We close with why it’s time to build (again). 🏗️ ⚛️ 🚧👷♂️🛠️

🎧 Listen on Spotify

If you prefer to listen on Spotify, here’s the feed:

🎧 Listen on Apple Podcasts

Here’s the podcast feed on Apple Podcasts:

📺 Watch on YouTube

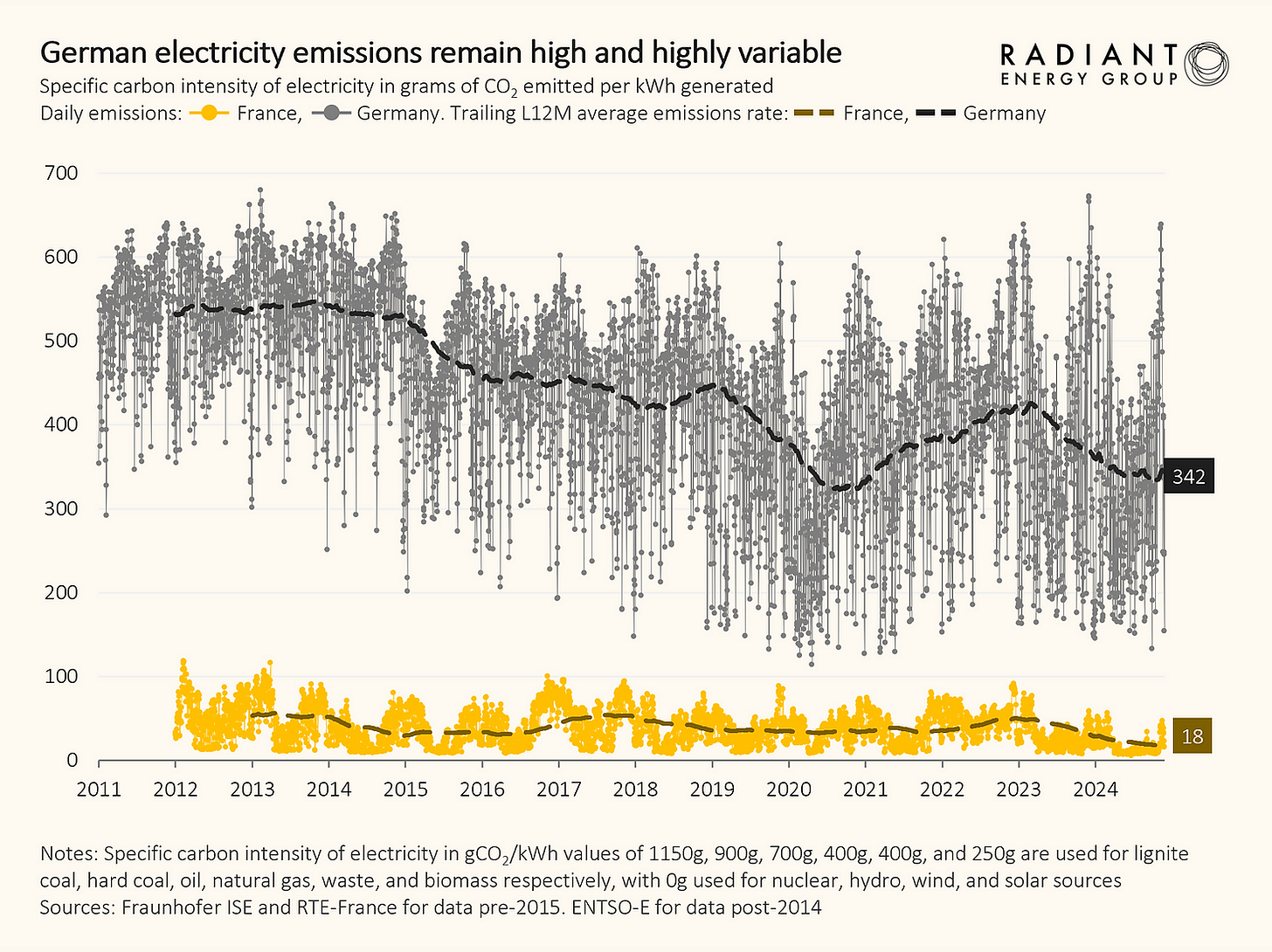

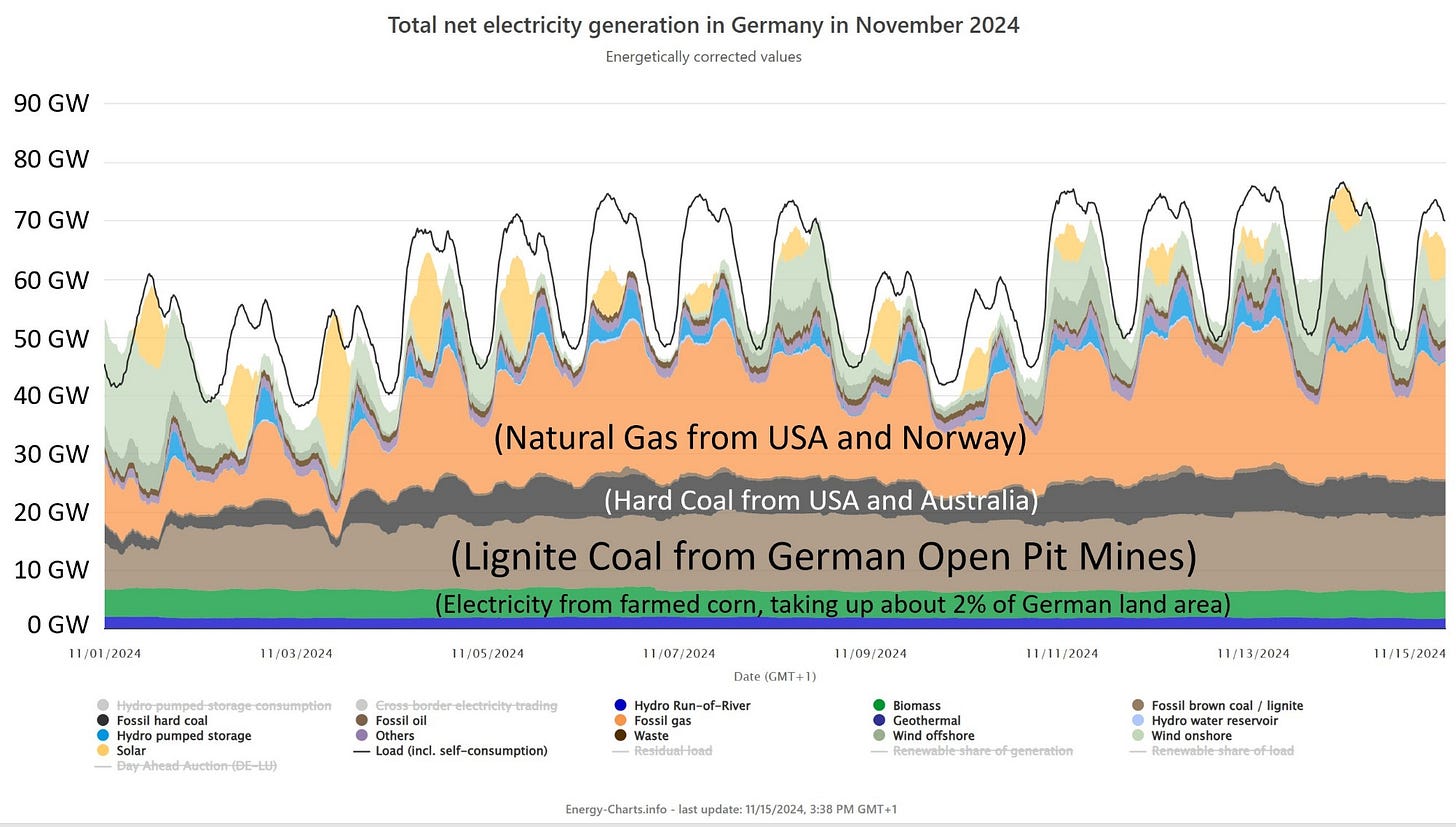

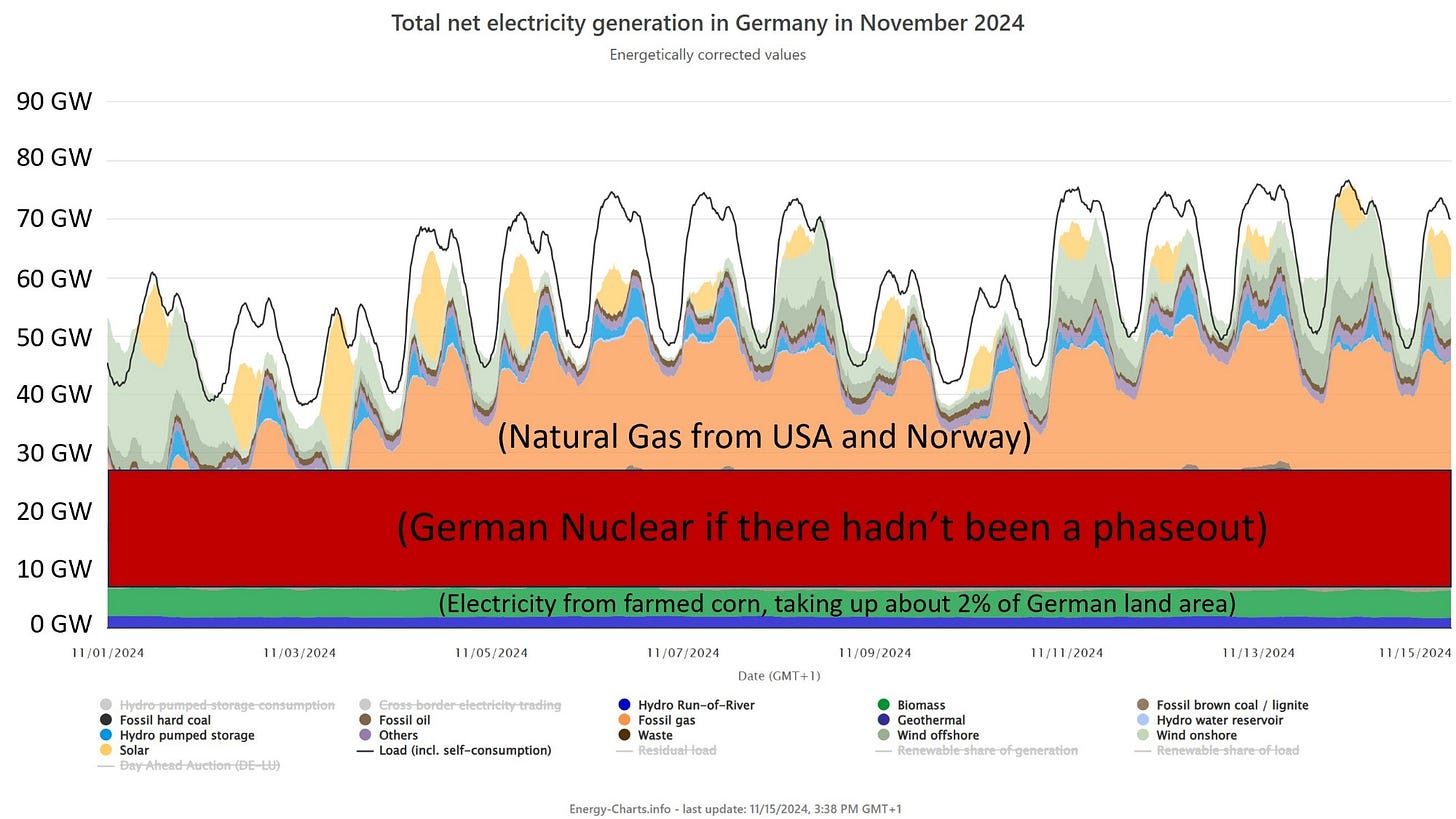

Oh Germany…. 🇩🇪👇

📄📄 Further reading by the Radiant Energy Group

⚛️⚡️🔌 More of my writings on Nuclear

Rebranding nuclear power? How can we fight the double standard?

‘The Energy of Tomorrow: The Promise, Failure, and Possible Rebirth of Nuclear Power’

On December 31st, 2021: ‘Germany pulled the plug on three of its last six nuclear plants’ 🤦♀️

NuScale: US regulator will certify small nuclear reactor design for first time ☢️🇺🇸

‘UK to put nuclear power at heart of net zero emissions strategy’, Nuclear Power Edition

🗄 More podcasts from the Archives 💡

🎧 The Cost of Glory with Alex Petkas: Timeless Lessons from Ancient Greece and Rome 🏛️🏺📜 🏹⚔️🦅⚖️

🎧 Going deep on Constellation Software with Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI)

💚 🥃 Enjoyed this? Want more? 👇

You can become a paid supporter to get access to paid Editions + access to the private Discord + Zoom Q&As with me + support the recording of more podcasts:

🤖 Raw Machine Transcript 📃

Liberty: Mark, thank you for joining me again for part two.

Mark Nelson: Good to be here.

Liberty: We talked just one month ago and Uh, we were just running out of time when we started discussing new nuclear power plant builds, want to come back to that. But I think before we go there, the elephant in the room, the big thing that has happened since is the new U. S. administration. I'm very curious what you think about how this may affect energy in general, nuclear specifically. I think we can discuss all of that. I'm also very curious what you think about Chris Wright, the new, energy secretary, which seems to be like, from what I can tell, the opposite of a Dr.

Oz type of nomination. He seems to know what he's doing, but I'm curious what you think.

Mark Nelson: So Chris Wright is well known in the oil community, especially the Denver oil and gas community. My, uncle has an oil and gas company in Denver, a small one, and he works with my dad. So I was raised in and around oil and gas and just it like a petulant teenager when I insisted on doing low carbon energy and went off to nuclear to work on that.

But my whole life has been funded by oil and gas, my scholarships at Oklahoma State, even my scholarship to Cambridge to study nuclear. was paid for by an oil and gas executive, retiring chairman and, CEO of Phillips Petroleum, who was okay with me using his money to go study nuclear engineering for climate reasons. It was my main motivation at the time.

So to hear, people talk about Chris Wright is to hear about his relationships in the oil and gas community. First thing I'll say is I heard a single bad word from who knows him. That's a pretty good sign, and I don't think it's just people trying to suck up for the new administration.

So, Chris is an entrepreneur, his business, Liberty Frack,

Liberty: Yeah, I'll try not to let the name bias me too much.

Mark Nelson: Yeah, no, it's not Liberty Frack anymore, it's Liberty, it's uh, Liberty Energy. And I heard from a friend of his about the insight here, it's that, You should name your company off of what it's providing rather than specifically what it's doing in the narrowest sense.

So in this case, Liberty Frack is one of the, largest, oil and gas services companies specifically helping with, hydraulic fracturing. Now, my dad for a long time has been pissed off at the world that, one, people care so much about as opposed to other well completion techniques. Fracking is just one of many well completion techniques people have always had and always dealt with.

It's just that the specific application of fracking horizontal drilling in particular rock formations in America has allowed us to revolutionize fracking. our oil and gas industry and become the world leader in both natural gas and oil production, thereby making fools out of a lot of people who predicted decline.

So Chris Wright is part of this optimism, this wave of innovation, made fools out of all the doomsayers who said that we could never produce That much oil and gas ever again. Chris is a friend of Harold Hamm, one of the last of the great independent oil men sort of the king of North Dakota tight oil place.

Harold Ham has been a long time friend and supporter of Donald Trump's political ambitions. And that was one of the key connections that helped get Chris Wright in the front row of seats for joining the administration on energy. Chris is interested in all energy types. He does apparently feel that all energy types have a role to play.

Trump doesn't like wind, especially offshore wind, so I'm, that's probably not going to be a particular focus of the administration to figure out how to get Europe's wobbly state oil and gas companies all the contracts to build offshore wind on American but besides that, Chris Wright is an all of the above energy guy.

A lot of people have been Pointing out that Chris is, or was, until he's going to have to step down, I presume, a board member of Oklo, one of the advanced nuclear developers. People have asked me, does that mean that Trump won't be interested in big of the is Behind this question is that a few weeks before the election, Donald Trump went on Joe Rogan's Incredibly popular podcast and said that he likes the small reactors and he voiced concerns about nuclear war But was a little a little unusual in how he phrased it leading to a lot of confusion about whether Trump was actually pro or anti nuclear.

is pro nuclear. He has been pro nuclear for a long time He likes things that are powerful. Nuclear is powerful Trump further confused people listening because he said that France Made a bunch of nuclear reactors in a hurry, but then the nuclear reactors got too big and too complicated So we need to go back to small reactors the reactors that France made did indeed start smaller than the ones they ended up getting slower and worse at building France started building out a huge number of 900 megawatt units When the oil crisis hit.

So 1973 and onwards, they were starting four or five new 900 megawatt units per year. And after about five years, they were completing four or five 900 megawatt units per year. Those are the reactors that, that seem to have influenced Trump to say that he thought the reactor should be smaller. Now, the larger reactors would be the 1300, 1500, or even 1700 megawatt reactors that have been much slower in construction.

So the choice of Chris Wright, for those who heard the France comments and thought that Trump meant that he only liked small reactors, and seeing Chris Wright on the board of a tiny reactor company, that's raised the question, is the new administration going to be as serious as the last administration was?

in pursuing the restart of America's gigawatt scale reactor construction.

Liberty: just for context, for those not familiar with Oklo, I think they make liquid metal cooled fast neutron micro reactors, like 15 to 50 megawatt, right? Very, very small. And they don't make them yet, but

they want to make, them.

Mark Nelson: Yes, so 10 megawatt, electric reactors. So, that is quite small. And there's a number of competitors in that. 10 megawatt class. So one being the eVinci reactor from Westinghouse is 5 megawatts electric. Another is from Aalo Atomics, based in Austin, Texas.

That is a 10 megawatt electric design. So there's a number of reactors in that size class. When I asked friends of Chris Wright, what's the deal? Does he only like small reactors? I was told, no, he sees the need for all size of reactors in the right place. Here's some context for people coming in from oil and gas.

of the growth in American fossil fuel production is coming from the Permian Basin of Texas. That is DOMINATING new production in America. The limitation in the Permian Basin appears to be far distant production sites, well sites, that need between 10 and 15 . and 80 megawatts of electricity if they're going to electrify their production to maximize the natural gas that comes into the market and to minimize climate impacts for the investors that care. You are unlikely to go into an extremely dry region like the Permian Basin and set up a large number of gigawatt scale water cooled reactors. It's not impossible. And in fact, there's some interesting ideas behind how my one might pull that off. I mean, for one, the Permian Basin is producing an immense amount of fossil salt water.

So, ancient seawater that comes up from the same formations that the oil and gas comes from. So, there is water that has to be disposed and there are cost and geologic issues with disposing enormous amounts of water back where you got it. Putting that aside, If you were to have 10 megawatt scale reactors and they could provide power at prices competitive to diesel, there would be an economic case for these in a decentralized fashion without building out the power grid in the Permian Basin to keep production high while electrifying oil and gas production. Chris Wright sees the utility of this and it was evidently a major part of his interest in teaming up with Okla.

Liberty: You think this could also apply to the Canadian oil sands that use a lot of heat, probably natural gas right now.

Mark Nelson: Yes, it does apply to the oil sands. Oil sands are extremely thick, viscous formations where this thick oil is mixed in with sand and must be separated from it by heating up the sand and oil mixture. some significant fraction of the energy content coming out is spent on getting it out in the

first place.

Liberty: Yeah. I've seen it's like one to four or one to six X, the energy coming out.

And the Permian is like,

10X to 15X or

Mark Nelson: yeah, 15, 20, 25%. Of the energy You're getting out of the oil, you're having to spend on producing heat to make steam to separate the oil and gather it up. So the idea is that small reactors, that do not require you to go through the process of gigawatt scale development, which means the grid and restarting construction.

All things that I think should happen and must happen, to be fair. The argument is the small reactors allow this quicker, and for individual businessmen to make a private decision for themselves whether it's worth adding that nuclear power for their own uses on their own locations. That's obviously very appealing to the Texas based oil companies.

Liberty: I didn't know Chris before he was nominated. I've listened to a couple of long form podcasts of him and he does seem like into all forms of energy to him. It's like almost a. basis of civilization and we have a moral imperative to bring cheap energy to the masses and bring people out of poverty.

And like, he sees that as his mission. I'm curious though, secretary of energy, what kind of power does he have to actually change things? Right? Because seems very different, but do you think that in that position, he can really make a big difference in. Energy production in the U S and I guess somewhat ironically, if the U S produces a lot more prices could go down a lot, which would probably be bad for profits of some of these oil companies.

he says, he doesn't care about that. He cares more about mission, but what levers does, energy secretary have?

Mark Nelson: It's almost too commonly said now, but the Secretary of Energy's primary mission is to assure the President that our nuclear weapons exist and work

Liberty: Yeah.

Mark Nelson: in the ways and in the numbers, counted upon by our defensive strategy. That is, the Secretary of Energy is much more about KTs, kilotons, than about, KWs, kilowatts, or kilowatt hours even. Having said that I'm going to push back and say, although the budget of the Secretary of Energy is made up by, National Nuclear Security Administration, that is, the nuclear weapons stockpile, creator and administrator, the Secretary of Energy has always had an important symbolic and practical role in steering or promoting, uh, Aspects of American energy. Under the last administration, with the loan office, the loan program office, LPO, in the, Department of Energy, there was an enormous amount of money and power vested in a small group of people to make American energy happen. Not all of that has been used, and very little of it was used on nuclear energy, despite the loans program office Openly inviting applications and insisting that they wanted to support nuclear more. The reasons for this are various one When the last administration started, nuclear was not, in many ways, ready for prime time. We were still in the slow down, shut down, maintenance, decommissioning mindset, rather than in the must build now, here's tens of billions of dollars of projects that we can use loan program office money on if we can apply.

So, the nuclear industry was in a sort of caretaker, shrinking state, and it's been very difficult to get it up to speed at the scale of opportunity that was made available. I was one of the weirdos that for a very long time has been trying to promote Gigawatt scale reactors in America. Some of our nuclear operating companies, until last year, were claiming we would never do it again.

Some of those same companies are now saying, No, actually we're interested, let's work on it.

Liberty: Did Constellation Energy actually change its tune? Cause I know they were in caretaker mode for a while.

Mark Nelson: Some of the nation's biggest nuclear operators have done a 180 in an extremely short period of time.

Liberty: good.

Mark Nelson: we are so happy to hear that. We welcome everybody to the gigawatt scale club. Let's figure out how to get it done. If the new administration is interested in gigawatt scale deployment, the government will still have a role.

Until we get properly moving, and that means say six or eight reactors ordered deep and started under construction, it will be very, and until we get halfway through or we start meeting timelines and schedules, Carefully said, it will be very hard to convince private capital to come in at the scale necessary.

That may be a role to be played by government loans. That's not exactly the same thing as a subsidy. That's saying if the nation wants to see us competitive with Russia and China on gigawatt scale nuclear deployment, then it's not so much a direct subsidy we need. We are asking for help priming the pump.

with multi billion dollar financing, and that the federal government work with states that are interested in hosting the next generation of American gigawatt scale nuclear. That's what I think we can expect from the new administration, conservatively, and what we may be asking for.

Liberty: Yeah. I think that's worth highlighting, right? you make a loan and you paid back with interest, and then you have a new infrastructure that creates all kinds of economic activity and tax base and all that, like it's an investment for the government, not the same as a subsidy that you never see again.

Mark Nelson: Now we're still asking for help putting together the right balance of risk takers. The nuclear industry has squandered the that we hope to build up with the most recent builds of nuclear. One thing that we can do is come very humbly to big capital and say, here is specifically things that went wrong, when it went wrong, how it went wrong, and here is our plan to fix this thing and this thing and this thing.

One of the most basic things is the last time we built gigawatt scale nuclear in America, we started building. without having the detailed design completed.

Liberty: Vogtle, right?

Mark Nelson: We also started construction with the assumption that we would get a lot of wisdom and learnings and experience from the Chinese who were building the first couple. That ended up not being the case for several reasons, but it was the scheme. It was the idea we would build First of a kind in America that wasn't truly first of a kind because we were learning from overseas construction.

There ended up not being a terrible amount that we learned that helped us go faster. Here's another thing. We've got to have absolutely extreme focus on the quality of the supply chain at gigawatt scale nuclear construction before we get started. And during construction our supply chain infamously collapsed when building Vogel and Summer nuclear reactors.

We had designs that ought to have allowed, in best cases, four or five year construction. Instead, these modules were not fit for purpose, either rejected or had to be rebuilt on site after being shipped to the construction site. So the promises of module construction are still there. We just have to make sure our supply chain has learned these lessons of Vogtle. Having said all this, because of the boom in electricity demand We should have an excellent market signal and long term planning for the electricity regions that don't have wholesale electricity markets, so the vertically integrated utilities. There's already a very long term signal in the planning process, working its way through the pipes of an enormous amount of demand.

on these southern utilities, which then the southern utilities have to propose to their regulators how they would like to build power plants to satisfy that demand. Here's what I think we're going to see. We're going to see a lot of places say yes to new electricity demand in the short run and have to satisfy that with natural gas power. I see, hopefully, an integrating of short term natural gas boom and long term Gigawatt scale nuclear construction, co located, so that the nuclear can get constructed over the course of 10 years from planning to completion for the first set of new gigawatt scale reactors. And that the new gigawatt scale reactors can take over from the base load natural gas generation.

Or, you could add more industrial production or data centers to that location as the nuclear came online. I don't know if natural gas will always stay cheap. It's obviously the policy of the incoming administration to make fossil fuels as cheap as we can without destroying all of American, oil and gas profits and eventually production. Oil and gas in America has always had a weird tension with prices needing to be low for growth, high enough to not ruin the oil and gas industry. This means the oil and gas industry has often been divided on, against administrations that are supposedly oil and gas friendly. Because nothing kills an administration than high gas prices at the pump.

That is devastating to an administration, yet you could have oil and gas companies backing an administration that's pro fossil fuels that sees its life on the line if gasoline prices go up. It's a weird tension. And there's only certain levers that can be pulled in the USA because unlike countries with a nationalized oil sector, the government has limited direct power over what oil and gas companies do in America.

There is not particularly strong ability for oil and gas companies in America to coordinate. Whereas in other countries, it's a matter of a government policy to tell the oil and gas company what to do within the bounds of its contracting and international partnerships. Oil and gas is decentralized in America. We're about to find out how the tension between oil and gas profits and oil and gas high production get maximalist government. And a, uh, all of the above oil man turned energy secretary.

Liberty: On pipelines and transport. That's something that's been kind of stuck for a while in the U. S. And I know with Canada, you think this is also all going to change? Like LNG exports, pipeline, everything is, is everything going to happen all at once? Or is it the kind of stuff that you talk about on the, on the campaign, but then it's very hard to actually make happen?

Mark Nelson: I see energy exports as one of the few things that there's going to be total agreement on in this administration. LNG coming from America, going out to the world is not necessarily the threat to domestic energy prices that some people tend to think. here's the reason why Natural gas exporters need the largest price difference between domestic gas and foreign gas. So it is in the interest of companies that export natural gas to see prevailing low natural gas prices in America.

Liberty: Hmm.

Mark Nelson: Rising gas prices in America seriously erode that price difference because natural gas exporters have to actually buy and bring natural gas to their export terminals.

Then they have an energetically expensive process of liquefying the natural gas. Something like 10 percent of the natural gas is used to liquefy the natural gas. And then they have to ship it and they lose a bit more on the ship. And a little bit more in the regasification process on the edge. So you need a large price delta to make really good money and make make your money back in a reasonable amount of time on the multi billion dollar expenditures required to set up liquefied natural gas export terminals.

So, LNG exporters want to see cheap gas in America. They want to see as much as you as possible in America for that reason. A since the dawn of the oil and gas industry in America and in the world has been Overproduction when new finds are opened up. That leads to crashing prices that do not pay back the investments required to have drilled the wells and completed them in the first place. Even though it seems good momentarily for companies to have such cheap feedstock, it makes for very unstable supplies as a lot of people go bust quickly.

So, I think Chris Wright comes well recommended by people I trust. He It was greatly celebrated by the energy maximalist community as one of our own, I suppose. And I saw a lot of geothermal guys who come from the climate hawk world. So, renewables and climate policy dominating almost any other, priority.

Among that community, there's a lot of support for Chris Wright. The pushback is gonna be from people who attack Chris Wright for not prioritizing climate change above all.

Liberty: And he doesn't seem to be the biggest fan of EVs. In both interviews that I've heard, he mentions something that It seemed incorrect to me, the numbers I've seen that are different. You said something like, Oh, EVs, it takes 75,000 miles to repay the energy debt of battery in the extra manufacturing, right?

And so they're not a very good deal. They, they don't save much oil or energy numbers. I've seen are more like, you know, 25K at the, the U S grid mix average or where I live in a hundred percent hydro is maybe like a year, right? So it seems much better than what he's saying. I don't know if he's seen old numbers or he just doesn't like EVs or That's the one thing where. was more in disagreement with him. but I may be wrong, right? Like maybe I, I don't have the correct numbers.

Mark Nelson: Electric vehicles are here and they're gonna spread. And by here I mean on the globe. What China and China's battery makers are achieving with electric cars is extraordinary and we can say all we want in America that electric cars aren't coming. The rest of the world is going to get them. There's a lot of countries without oil.

To them, if they're importing either oil or, fossil fuels for electricity generation, they see it as a lot less of a cut and dry thing than you might in America where we have all the fuels. And we have a limited ability to actually build power plants in many places. If you're in the rest of the world that imports oil, To fuel cars

Or imports finished products like gasoline and diesel to fuel cars and trucks. The crashing price of electric vehicles and of the batteries in them is going to lead them to do, to make the same decision China did, which is that better to be electrifying your transit and dependent on fuels beyond oil than to be dependent on oil and gasoline and diesel imports if you're not already self sufficient. Norway is an example of a country that is an enormously important oil and gas exporter in Europe, where new cars are almost 100 percent electric vehicles. In their case, they don't want to use any product that they don't have to, and they have abundant hydro, or they used to have abundant hydro. That means that the incentive to get electric vehicles is extremely strong, both on a policy level and in a practical level. Norway does not get as cold as many other places. It's by the ocean, and the warm Atlantic makes for a somewhat more mild climate in Norway than in other places. But as batteries continue to drop in price and in energy intensity and in materials usage, we can expect that to be an enormous advantage for electric vehicles.

For me, as a nuclear guy, electric vehicles are demand.

Liberty: Hmm.

Mark Nelson: Nuclear stopped competing against oil for electricity production, Back in the 70s with the oil shock in 1973. That was the, that was the end in most places of nuclear competing directly with oil for market share and electricity. Oil and gas, natural gas, is often produced together and natural gas is a competitor against nuclear for market share and electricity. But I like to think that in a world that takes electricity and grid reliability very seriously, That's going to be one that both builds nuclear and electrifies some portion of transit. As batteries get smaller, electric vehicles become extremely compelling for consumers.

Liberty: Yeah. And they're a good match with nuclear too, since if you have robust baseload, you can charge at night on that nuclear power. last thing I'll say about electric cars too, is that. Any comparison, it's not a static target. Like as you say, as, manufacturing gets better, as maybe some of those manufacturing plants on cleaner power, the batteries get cleaner, the car itself as a energy omnivore that can take any source over a 15 year life may get cleaner over time as the grid gets cleaner.

While the internal combustion engine probably gets worse over time. Like the old clunker probably doesn't get all the maintenance and it gets much, much worse over time. So I tend to, Like, EVs is better than Chris Wright seems to. We'll see what the new administration policies will be there.

Mark Nelson: Well, look at this. Nearly half of each barrel of oil produced in the world is going to gasoline. Another 20 25 percent is going to diesel and kerosene for trucks, buses, and trains. for trains, if they're not electrified, and kerosene is primary component of jet fuel. If you start electrifying transit, but you don't burn that oil for the electricity, then you do the growth scenario for consumption of oil. I can see why it's very difficult for people in the petroleum sector To get on board with the idea that electric vehicles are the future because to embrace electric vehicles is to sharply reduce future demand for oil and gas.

Liberty: every electric car that goes on the road is demand destruction for a decade, two decades.

Mark Nelson: Sorry, I should say oil and gasoline. It gets complicated when oil and natural gas are commonly found together. Because if we don't need the oil and the price for oil goes down, then you are going to see some trouble with natural gas because in some ways oil seems to be subsidizing. natural gas On an energy basis, on a BTU basis, oil is several times the cost of natural gas in North America. Natural gas, on a BTU to BTU basis, is about, say, 15 a barrel versus oil's 60, 70, 80. That is an extremely sharp difference. And it shows how, to some old oil man, including Harold Hamm, gas is a waste product that you run into when you're trying to find oil. Only some of that cost advantage is going to be there permanently because of oil's utility, in the end, Oil's utility for, say, plastics.

In America, a lot of plastics are made from natural gas, because it's so cheap compared to oil. Oil is like the proverbial bison that the Plains Indians used every single part of. Every part of that unit of volume, 42 US gallons, the barrel of oil, ends up getting used. I'm actually pleased to say that I'm going to do an entire, decouple Oil masterclass with Chris Keefer coming up and we'll go over a number of these topics.

But for now, just to say I have been at my strongest disagreement with other allies on energy, that maximalist energy crew on the issue of electric vehicles. And in the end, it is inescapable. If electric vehicles start dominating, demand for oil must go down.

Liberty: Hmm. And there's no way to, I don't know enough about how that raw barrel of oil gets split into like, can you get more diesel out of it, say, and then like just change how you crack the, the refineries are

set up

Mark Nelson: You can do anything. It may require expensive investments at existing refineries, to change over to the new ratio of outputs. You very carefully set up refineries for a very specific ratio of outputs.

Liberty: It's not like a lever you can pull, right? That the whole thing needs to be

Mark Nelson: It's not that simple. And if you want heavier fuels, you're at a particular disadvantage. If you're doing a lot of your work with domestic light oils, the oil coming in from Middle East tends to be heavier crudes than our oils that we're producing from tight oil place. That means that it's going to be doubly difficult to both change the output of the refineries to reduce the amount of gasoline we're making and also do it in opposite direction to our advantage with our mixture of crudes that we're making in the U. S.

Liberty: One more question I had about the new administration. Since we last talked, there seemed to be some, regulatory problems with Big Tech and their nuclear deals. I think, FERC, F E R C, AWS and like Do you think all that's going to change now? They put new people in, place there?

Or is, there I know, so much energy in the system that it's not likely to change.

Mark Nelson: Nobody in power wants to be in power when we mess up the grid. The thing that seems to have turned around California's Governor Gavin Newsom on Diablo Canyon was experiencing a tiny little blackout in the summer of 2020. And realizing that he was going to likely be in office during the shutdown of Diablo if he won another term.

And I think that scared him and his team into realizing that they had to explore keeping Diablo or risk their political fortunes on a blackout, which may or may not be connected to Diablo going offline. They would definitely take the

blame for it. So, electricity is something you don't mess with as a leader.

And I think a lot of attention is being paid after the blackouts in Texas. The recent ruling was against AWS's claim that because their deal to move into a nuclear power data center at the Susquehanna nuclear plant in Pennsylvania did not involve electricity on a transmission grid, that therefore they should not have to pay the grid its 10, 11, 12 dollars per megawatt hour.

On of the nearly 100 a megawatt hour that Amazon was said to be Paying the nuclear plant owner for power. I was sort of split on this, on one side I want to see nuclear get the most money possible, and I want to stick it to all the people who said that we don't need those nuclear plants, let them shut down.

And I like to see them turn around and say, no, what we meant was they're so important and so valuable to climate that you can't allow the data center to just buy up all the power. I love watching that. It's like getting revenge. However, it is not. Undeniably true that the nuclear plant is not allowed to operate if disconnected from the grid. So to say that the user of nuclear power is doesn't need to pay for the grid when the nuclear plant itself requires the grid in order to operate. That's a little cheeky. And I can see why that might be ruled against. Another thing is if the grid was set up a certain way and paid for by customers and cities a certain way, there's an enormous amount of shifting of flows of power.

If you suddenly take A million people's worth of nuclear power and shunt it away from the grid and say we're not putting it on the grid. unless you're getting rid of a million people in some of the cities and towns that used that power in the past You've got to send power to those people somehow Through likely different transmission

channels,

Liberty: that makes a lot of sense. They want the benefit of the grid without paying for it, right?

Mark Nelson: which means reworking the grid in order to shunt power off its previous path while shunting power from a nuclear plant that requires the grid in order to operate.

So there you go. There are the issues. I think that Amazon's going to find it worth doing that deal regardless of whether it pays an extra 10 percent to the grid operator. I'm okay with that. Microsoft avoided this problem completely, knowingly avoided this problem by simply paying the nuclear plant owner, to put the power on the grid and then to withdraw a certain volume from it at certain times without requiring that power to be stuck behind the meter next to the nuclear plant, Three Mile Island nuclear plant.

Liberty: think this brings us to new builds, because These are scarce assets. kind of found the few that were left, but now if they want to power these big AI data centers, if we want to electrify parts of transportation, all the heat pumps that are coming, parts of the oil industry, if they want to decarbonize a bit, electrify, like all that stuff that's coming online, where are they going to find all that new power, that new capacity?

my question is like, let's imagine the scenario where this works, right? what's the way to do it? looking back, I see that it seems to be places like France or even the U S at the time, you need a kind of a program, right?

where you have many reactors. In the pipeline where the supply chain can build up and see that this keeps coming for a long time and it's worth, building up all that capacity, right? So what would that look like in the U.S. what do you see as the way to do that to have all these new bills that, are on time on budget, like what's, what's the way to get there?

Mark Nelson: Well, first of all, France was important by, pooling tens of gigawatts. of demand The USA is so large that an equivalent program is only a tiny percentage of the nation's power. So if you're building these large devices and you need to hit a certain scale of construction in order to learn how to build them well, series construction of the same design over and over, America's large enough that we can achieve a France scale program by volume, not a France scale program by percentage of the nation's power. And that will still be very useful to America's future. We don't have to convert to 70 percent nuclear in a single generation in order to put the U.S. on a much better trajectory, whether your goal is climate or energy dominance. So, that's the first thing I have to say. In France, you had a state monopoly company for electricity production and distribution, where to get to that scale, it had to truly be a top down national program.

And you can achieve those scales in America without it being a top down national program. we already have an enormous amount of existing infrastructure and locations to put nuclear power One of the most important aspects of the top down, centralized nuclear program in France was forcing certain areas to take on nuclear plants.

We won't have that issue in America. You could simply just double the nuclear plants across America that have cooling water supplies To host and land area to host more reactors and those are communities where by definition if you've been living there for 40 years you are at least that okay with nuclear being in your backyard. If you have been living next to a nuclear plant for 10, 20, 30 years and you don't like it, it's a little bit weak to say it's more reactors that I have a problem with, but not so much that I moved away from the existing reactors. So, not saying that there aren't reasons to put in crucial infrastructure over some community objections, but you're not going to need that state force like you did in France, where they had to sometimes come in at night, set up bulldozers in a fence perimeter, and fight off the locals.

Liberty: Wow. I didn't know that.

I want to underline something you said, because I, I didn't know about it until maybe a year ago or something. And I think, I don't think most people know enough about it. the existing nuclear plants in the U.S. have been designed to be expanded and could fit more reactors.

a lot of the process and the permitting and the construction and like the infrastructure already exists, the rail, the water, lot is already there. So it's a lot simpler to, increase capacity at existing plants than to start new builds all over. that seems to be the no, no brainer place to start.

Mark Nelson: We are limiting the future of America if we never think beyond existing nuclear plants, but we have enormous headroom at existing nuclear plants. We could Nearly double American nuclear capacity with existing or nearly existing nuclear sites. By nearly existing, for example, we have several places around America where we started building nuclear and never completed it, but we got a lot of the crucial infrastructure in place. So yeah, uh, I think that it's a great start, but we shouldn't limit ourselves to only thinking of Brownfield power generation sites, so places that have already hosted large power plants that were not nuclear, are another great candidate. And then we have to be ready to think in terms of greenfield sites eventually, if we're going to build out energy for a lot of future growth. China is currently struggling a little bit to add new nuclear plant sites. It's not clear why there's been such a limitation. Nuclear. Programs were seriously pared back after Fukushima Daiichi. I think a lot of people don't realize just how negative China was on nuclear expansion for a little bit. We, like, have a missing generation of plants that were started and then scrapped

Liberty: Hmm. I didn't know

that.

Mark Nelson: the years after Fukushima.

Liberty: I've seen the graphs where they make plants in like four or five years and they seem made a ton of them But I I didn't even notice that it kind of slowed down or stopped

Mark Nelson: yeah, you can see on satellite imagery that were started and never allowed to get into full scale construction And you can see parts of nuclear plants that were sitting there for a while and either have been moved or just left to rust.

Liberty: And have they restarted since?

Mark Nelson: they've started expanding nuclear plants again. There are a few new build sites, but they seem to be exclusively along the coast. There's almost no nuclear plans for inside the country.

And at one time there were a lot.

Liberty: Why do you think that is?

Mark Nelson: Just an extreme conservatism around nuclear. I don't know if it's coming directly from the top, from Xi Jinping, who would have been coming into his full power around the time of Fukushima Daiichi, which, remember, is a lot closer to China than it is to Germany, where it also did a number, it lobotomized, The German pro nuclear parties, it completely destroyed their ability to think rationally and protect their own country's future.

And that was half a globe away. China was right there.

Liberty: I think that's a perfect segue into Germany. That's the one that angers me every time I think about it, and I'm curious what you think about We discussed it a bit in part one, the potential for a restart, but even since last month, I feel like this sentiment has keep moving and everything keeps moving so fast around the world.

what's your current thinking about Germany

Mark Nelson: Germany's coalition government lasted not even a single full work day. beyond the election of Trump. One of the funny things online, I, my sources in Berlin tipped me off that the government was about to fall. I posted online and a bunch of Germans are like, look at this idiot American, thinking there was anything to do with Trump getting elected that caused the government to fall.

And at the same time, I'm thinking This has got to be some of the least politically sophisticated people I've ever heard of. Obviously A leader getting elected who is countries slacking on their NATO obligation, is willing to dissolve any allyship or make any deal with any supposed enemy country if he thinks he gets a good deal.

That obviously matters if you're minority party in the coalition government, what you think is going to happen if there were elections, if you could trigger a governmental collapse. So, Germany saw that a new world was coming and the existing coalition was probably not going to be the one to carry it forward.

That exacerbated or set extremely solid lines for the parties that wanted to continue fiscal discipline in Germany, but also supported the nuclear restarts. And I think that that was a crucial part of why the government fell the very day that results were being announced in America. It to coincide with one of the worst days of renewable energy ever in Germany and in the European continent.

Liberty: right. They've had like a month of almost no wind and cloudy skies and,

Mark Nelson: During the few hours that decided the collapse of the German government, the total of renewables on Germany's grid was about 70 to 80, or at least wind and solar. There's the biogas, but putting that aside, and there also some heritage hydro left over, but for wind and solar, the future basis of Germany's energy system, according to the government, there was only about 70 or 80 megawatts during the low ebb of power on the day the government collapsed, but they have 166,000 megawatts installed that they're paying for.

So they're paying for 166,000 megawatts install capacity of wind and solar. And during the hours when the government fell, it was just below a hundred megawatts or just above

that is a

fairly extreme gap,

Liberty: and they paid over half a trillion euros for it.

Mark Nelson: which means keeping up that quantity of power plants and keeping a hold of that quantity of fossil fuels.

in order to survive those conditions, which of course I believe Germany will always try to survive those conditions. It just means that they will have to have increasingly outlandish energy expenditures on more rarely used fossil fuel equipment while still paying high prices to develop wind and solar as they are a country with quite poor wind and solar resources. All of this to say, there's now a A window of opportunity for the nuclear plants to survive in Germany. The current state is that there are two nuclear plants in Germany that could come back online within a year or two. And then there's six more that could come back online before 2030. or so depending on how quickly orders were placed and how quickly work proceeded at the plants, if the decision was made to turn them back on.

And then there's a number of other plants that would be something like, a very Advanced brownfield site where you have a lot of equipment in place. You can reuse a number of structures and local know how, but you would need to rebuild the reactor system within Repaired or existing containment building and in cases you would need to rebuild the cooling towers that have been destroyed All of this is cheaper than not doing it.

All of it is expensive A better future for Germany than not doing it. And all of it is cheaper than building nuclear from scratch.

Liberty: What a disaster. had them and they threw them away and it's not an easy reversal, right? There's like a couple years for the ones that are perfect. that's still a while, but until the end of the decade for the others, they should absolutely do it. But if, is it cheaper to build a time machine and just go back and not do it in the first place?

I don't

Mark Nelson: That's the tragedy of the elections across Europe of 2020. Green parties got into energy ministries across Europe. And the only reason green ministers wanted that power was to enforce nuclear phase outs.

Liberty: Changing gears a little bit. One thing that I hear smart people on both sides and they're kind of both convincing to me. And so I'm curious what, your take is on, solar power, right? So we know the downsides, like if you were very far up North, like, in Europe or, because it's intermittent, but the argument I hear from very smart people is like, doesn't matter.

The cost keeps falling. If it falls enough. And batteries keep falling enough. At some point it's going to win. At some point it's the one that's going to dominate. And so anything else we do in the meantime, doesn't matter because that feels like. Taking too many lessons from Moore's laws where they don't apply, right?

Because even if the panels are actually free, all of the stuff around it, the labor, the materials, the concrete, like building the, the grid, the transmission, all that is not free. And so it feels like there's a floor price on solar power that's still fairly high. And then the batteries kind of same thing, right?

There's only so much it can fall, but is that all there is to it? Are these people just like taking lessons from Moore's laws where they don't apply? Or is, am I missing something? Is eventually going to be much bigger? If It just needs a decade or more of development. Or are we nearing the end of solar prices going down?

Because a lot of that was kind of like China trying to dominate that sector and subsidizing. All that is kind of swirling around in my head and I'm not sure what to think. I'm curious what you think about it.

Mark Nelson: The price declines in solar have been almost exclusively because of scaling up In Chinese manufacturing and Chinese internal consumption. It's going to be so interesting to see what happens when China starts exposing solar farms to market prices of electricity. Regardless of what solar people say about nuclear or other power sources, nothing competes so viciously and brutally with solar farms as other solar farms.

Liberty: Hmm.

Mark Nelson: Batteries have only a limited ability to stop solar farms from defeating each other economically. Now, one of the things you can say is that solar farms don't have to respond to any aspect of supply and demand. Ignore that. Solar, just do whatever you can. We will reorient the grid and even society if we have to, to make the best market conditions to build out solar.

But at some point that optimization runs against other really important political imperatives. Wind is not really getting cheaper in most places. It's really struggling in a lot of places. In the end, because wind turbines pop up really high, they're subjected to engineering forces and to public relations. traps that, that solar does not, will not ever experience. Wind is suffering greatly here, and in the same way as solar, wind competes with wind brutally. Can solar panels get cheap enough to solve this? I think I agree with you. It's the rest of the stuff around solar that is going to be a major limiting factor. Solar build out in Texas is probably going to end up looking like an S curve. It's just you know, saturation at some point. We just don't know how high that's going to go in a world of the Permian basin needing every bit of electricity it can get in order to power operations and a great difficulty in building anything but natural gas turbines.

I could see there continuing to be solar growth in order to save fuel from having to be burned by natural gas plants that otherwise are okay, altering their production up and down. I don't know where Europe is going to go with declining price in solar because that's a very limited utility in a continent where a large amount of energy demand takes place when there's very little sun. If you build a bunch of batteries, the only economic case for those batteries is that they get used in ways that are not compatible with just filling them with energy. at solar plants with solar power. If you build batteries, they will survive by filling themselves with whatever's on the grid whenever they think is best to fill, and unless you pass a rule that says batteries must avoid charging when the marginal fuel is natural gas, then, in which case you would probably kill off a battery industry overnight, like battery installation for grid purposes overnight in a country if you made that rule, then you're going to have batteries raise total baseload demand.

That's what batteries do when you bring them into a place, which means that things that can provide predictable baseload power supply do well compared to, say, the solar that you would think is the reason to build the batteries in the first place. So, batteries smooth out demand and supply to be more baseload like, which advantages baseload capable power plants. Just because solar is very cheap does not mean that solar benefits the most Or provides the best economic case for batteries.

Liberty: when I understood how the ROI on batteries is very high, if you have a small quantity of it. Because you balance the grid, you arbitrage basically. But if you want a very high renewable content grid with tons of batteries to back it up, those batteries that are used only in tail events, once in a while, are sitting there Basically idling most of the time.

And so the ROI on those batteries is extremely low, right? And so the, the economics of battery deployment, it's not like a, a straight line, but it's, this curve where it becomes very, very difficult to justify more you have, the more renewables you have in the grid,

Mark Nelson: If you want to get extra cheeky, something you can throw back in people's faces is what the carbon payback period is for batteries if you infrequently cycle them. Because the lifespan of the battery does appear to be in many ways insensitive to the number of cycles. So you can cycle extremely frequently and have a battery last nearly as long as one that you don't cycle. While that's true, it means that the carbon invested in the battery is amortized out of the number of cycles and the amount of carbon you save on the grid for each cycle of battery, and you just cannot do much better than even a natural gas peaker if you infrequently cycle batteries.

Liberty: Hmm. That's a good point.

Mark Nelson: Even if you're filling them with carbon free power. So, one of the ways to take care of this is to make sure that your local carbon goals don't actually include full life cycles and therefore it's other people's problem and you can keep blaming China for making all this nasty pollution while you, consume the batteries and the solar panels that they power with their coal plants. On the other hand, if we internalize those metrics, we see that you need To minimize the carbon impact of having to store electricity, you need to deeply cycle batteries a large number of times before they wear out. And that needs to be carbon free or nearly carbon free power that you cycle those into those and out of those batteries.

The batteries are going to eat up 10 percent or more of the round trip electricity. So anything you store that does count as an increase in demand. all of this together, I think cheap batteries are a killer app for nuclear power.

Liberty: Hmm.

Mark Nelson: Traditionally, grid storage of electricity was built to work with nuclear plants.

Liberty: Yeah. Pumped hydro was, often paired.

Mark Nelson: Exactly. Cheap batteries are a win for nuclear.

Liberty: All of this is such an interesting systems design puzzle. And it feels a lot like too many parts of the grid are focusing on just their one thing, right? Oh, let's build a solar farm here and look at the cost of that one farm, but you don't understand how it affects the rest of the grid, the larger system.

Hopefully, I don't know if Chris Wright is the guy or someone can have a view of the whole thing and help, balance it out. In a smarter way.

Mark Nelson: You would hope that a system like in France is where there's an electricity near monopoly at EDF that is able to view all this, you'd hope that that could put together a total view that optimizes long term value for the citizens of France. Instead, EDF gets captured and Forced to make losses to undertake other goals that are set without any reference to welfare for consumers.

So, for example, EDF has to turn down their already paid for nuclear plants. Saving no fuel, but turning down their already paid for nuclear plants in order to onto the grid, often in the wrong times and places, renewables from outside energy developers that then EDF has to pay extremely high Subsidies to, while losing money themselves.

on Nuclear that doesn't save them any money to turn down and all of that while having to wait sometimes years to clear The debt on their books from all those subsidies they pay out because the government reasonably doesn't want the electricity rates to be jacked up enough to pay for the subsidized, wind and solar that was never even needed in the first place because they had enough low carbon power.

So let's step away from that problem and say that For all the hate that comes their way, vertically integrated utilities in America are in a dialogue. Is it a dialogue of equals? Is it a inferior to a superior? Or is it the reverse? Have these utilities captured their regulators? Have the regulators captured the utilities?

I've seen both arguments and I've actually probably seen both versions of that. In California, definitely. It seemed the regulators had captured PG& E and the other utilities and were forcing those utilities to run California off a cliff. In other places, I would imagine the balance is more equal or the utilities have the upper hand, depending on who the regulators are and which state we're talking about.

However, vertically integrated utilities in a western are required to look at the total income impact on the cost of delivering electricity, all in cost of delivering electricity over time to a mix of customers. If they build this power plant as opposed to this one, or build it here as opposed to there, or if they include renewables, does it save enough fuel and the plants that they need to keep running along anyway renewables? Well,

It might if there was a company only dedicated to taking in subsidies for renewables and developing renewables and selling off the power plants afterwards. That may make sense to that one company, but in the total view, total cost to consumers, you may not make enough money back in the absence of an external, uh, Carbon tax forced on the companies, forced on the state, forced on the citizens by a strong federal power.

You might not make enough money back for customers to save by having renewables compared to your financial losses at existing infrastructure. So, that is already happening, and in those places we're still seeing them build out electrification infrastructure. Um, electric vehicle charging, We're seeing vertically integrated utilities build wind and solar.

Not as much as wind and solar oriented people think they should, or even some people who model the total grid, but you're seeing it happen in a much more balanced view from the perspective of a total electricity perspective.

Now, France apparently learned at least at the moment the ministers put in charge of energy and finance are pro nuclear. for the moment. Also for the moment, a number of European countries are turning more pro nuclear as they throw out the people that put Europe in its energy crisis from 2021 to 2022.

That's very slow progress. And there's a number of countries that feel so insulated from those pressures that they continue to try to undercut nuclear at the European level. That's one of the reasons why it's so important that a country like Germany has internal balance on what it thinks on nuclear, because an enormous amount of damage can happen when people who don't They don't have an ambition to make money and do commerce.

their ambition is to interfere in other countries politics. When those people, those ideologues, are appointed to positions that don't seem that important to Germany internally, like ruining everybody else's energy policy, that, that's something that you can get true warriors. to go do as a meaningful career.

And in Germany, what we've seen for decades, the German taxpayer has either intentionally or unintentionally been funding the destruction of trans European energy. If Germany has even a single strong pro nuclear government, you would hope to have a disruption of the money and people going to mess up other energy policies around Europe and around the world. We'll see if it happens. In the US, when you say decentralized, clearly that can be used at many different levels. We have a laboratory of democracy and laboratories of commerce, the states, right? We have many different ways of regulating electricity. The deregulated electricity seems like some, in some ways it can become more centralized with giant companies bestriding multiple states.

That, answer to forces first and then the regulator second, maybe. Or then you have chunks of America where the old system is still in place and vertically integrated utilities have to present plans to a regulator and make a case that they deserve return on investment if they execute the policy as approved by the regulators who themselves are voted into office.

Which one decentralized? Which one's regulated? Which one's not? It's actually a sort of a weird use of words.

Liberty: Yeah

Mark Nelson: we don't know what's going to happen under this administration. We do know that after a several decade period of there being a bipartisan push to deregulate electricity, it's not clear whether that's in the populist playbook anymore.

And there are parts of the Republican Party in the U.S. that are pushing back against this idea of deregulation. Restructuring electricity and getting rid of vertically integrated utilities and the rate case model of building out the grid.

Liberty: It'll be fascinating to watch. I think that's a good place to leave it for today. Thank you for doing this. I always learn a lot when I talk to you, so I really appreciate it. I'm curious if you have any closing remarks, what's the takeaway the listeners should take from all this today?

Mark Nelson: I'm personally trying to see gigawatt scale nuclear get built in again in America. It's an extremely difficult problem. Not every single inch of earth is going to be the right place for gigawatt scale nuclear. And I would make that advice in some countries or in some regions. In America, where we have existing nuclear plants, With world leading operations of gigawatt scale nuclear, I think it's time to build like that again.

I think America has the right reactor designs, we have the right reactor operators, we have the right level of demand, and we finally, I think, have the willpower to act on that level. It's just about coordinating all those features, and I'm working to help coordinate them, and I will be working with anyone in any administration that wants to see America return to the style of nuclear construction that we were the first and best at and that became the standard around the world, especially in countries that are likely to be our commercial and political adversaries in the future.

Liberty: It's time to build.

Thank you.

Mark Nelson: Time to build.