Guess who’s back!

On his eighth appearance on the podcast, MBI (🇧🇩🇺🇸) joins me to discuss one of humanity’s most impressive achievements: The semiconductor industry.

We couldn’t talk about everything and it wasn’t meant to be a structured primer (for that, see below). It’s friends having a conversation, discussing what we find most interesting in the space.

We primarily focus on TSMC and Texas Instruments as these are the two that MBI has researched deeply. However, we also touch on many other companies as well as ideas and concepts that apply more broadly. And some big risks… 😬

And yes! Someone should definitely make a film about Morris Chang!

The purpose of this pod is to pique your curiosity about this magic polished sand. We want to encourage you to go down that rabbit hole (we have book recommendations at the end if you don’t know where to start). 📚🐇

We also brainstormed an interesting proposal to create a US alternative to TSMC (USSMC?). It’s in the podcast, but I also wrote it up below 👇 and further down are links to MBI’s semiconductor deep dives 👇

🎧 Listen on Spotify

If you prefer to listen on Spotify, here’s the feed:

🎧 Listen on Apple Podcasts

Here’s the podcast feed on Apple Podcasts:

📺 Watch on YouTube

🤔 Mag7 Semiconductor Insurance Policy Proposal 💰💰💰💰💰💰💰🏗️🛠️🐜🐜🐜🐜

There’s something we brainstormed live on the show that I think is worth highlighting here, because I’d love to see it happen:

TSMC is the most mission-critical company on Earth.

If we imagine an inverted pyramid with TSMC at the bottom, there is so much value in the world resting on it. In other words, if it were to disappear, pretty much everybody would be hurt.

The US Big Tech companies — known as the 𝓜𝓪𝓰𝓷𝓲𝓯𝓲𝓬𝓮𝓷𝓽 7 these days — have the most to lose because they are *heavy* users of semiconductor and they are incredibly profitable.

Because these trillion-dollar companies touch so many other parts of the economy, if they’re hurt, there will be plenty of pain to go around.

So you have trillions and trillions of dollars in market cap (and I mean that in the broadest sense of the term, also applying to private companies and governments, national security, etc) resting on one company.

It seemed to us that it should be a no-brainer for the Mag7 to create a consortium to try to create an alternative to TSMC. They could do a better job than the government trying to sprinkle subsidies and tax breaks.

The quickest path may be for Intel’s foundry business to be spun off and maybe merged with GlobalFoundries (AMD’s old fabs) to get more of that third-party customer service DNA injected in the culture.

Mag7 consortium members could start by chipping in $5-10 billions each and lobby the government for a streamlined and fast-tracked regulatory regime on national security grounds. Stuff needs to move quickly, not take 10 years in paperwork review.

Semiconductor talent from around the world could be attracted with higher-than-standard compensation and equity in the new startup that would have the potential to be the next TSMC.

That’s NOT an expensive insurance policy when you consider how many trillions of dollars would be impacted by a long-tail event taking TSMC offline (and sadly, that’s not a far-fetched scenario. China’s leadership frequently discusses the invasion of Taiwan).

The opportunity cost wouldn’t be prohibitively high since all these companies have net cash on their balance sheet earning a few percent.

📄🕵️♂️ MBI’s Semiconductor Deep Dives 🐜🩻🔍

Semiconductors: "To see a World in a Grain of Sand" (sub required 🔐)

Texas Instruments: Leading the Analog Chips Industry (sub required 🔐)

TSMC: The Most Mission-Critical Company on Earth (sub required 🔐)

🗄 More podcasts with MBI 🕵️♂️

🎧 Meta Platforms & Mark Zuckerberg: Going Deep with Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI)! 🕵️♂️🩻

🎧 Microsoft: Going Deep with Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI) 🕵️♂️🩻

🎧 Going Deep on Cloudflare and Datadog with Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI)

🎧 'Severance' Season 1: Going Deep with Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI)

🎧 Going deep on Constellation Software with Mostly Borrowed Ideas (MBI)

🗄 More from the Archives 💡

🎧 The Last of Us: Going Deep on HBO's Amazing Show with Matt Reustle and Tinkered Thinking 🍄

🎧 David Senra and Jimmy Soni: 'The Founders' Book Club on the PayPal Mafia 📖

🎧 Interview with David Kim a.k.a. Scuttleblurb (2023 Edition: Exploration as a Service)

🎧 Going Deep on the Energy Crisis and Nuclear Power with Mark Nelson (Part 1 of 2) 🔌⚡️💡

💚 🥃 Enjoyed this? Want more? 👇

You can become a paid supporter to get access to paid Editions + access to the private Discord + Zoom Q&As with me + support the recording of more podcasts:

🤖 Raw Machine Transcript 📃

Liberty: Guess who's back? Thank you for joining me, MBI, for, uh, what promises to be a very nerdy episode. Yeah,

MBI: one on CrowdStrike CloudFlare, back in 2022, I think. So in terms of nerd meters, I think we are already up there. So, you know, semi conductor is almost, you know, the flavor of the month. So it almost feels like we are engaging more into what's like in the moment, what's going on, you know, what's the talk of the town.

So maybe it's not as, nerdy these days,

Liberty: Yeah, it's much cooler when people are making money with it than when people are losing money.

But hopefully this can act as a kind of primer, right? Make people curious about it, about the aspects that may not be headline news, but are very interesting about it. so I was thinking of the first place to start, a good context would be to talk a bit about our personal history with semiconductors.

And can start, but I'm very curious about where it started for you. I'm old, right? So me, it started with my father's 386 running at 25 megahertz and four megabytes of RAM. and I had some friends with like Amiga and Apple to see, and like that, that was my introduction And immediately it was like a love story for me and I never stopped being curious about that stuff.

MBI: How old are you, Liberty?

Liberty: so I'm 42. I was born in 82. So that stuff is like early 90s.

MBI: right.

right.

Liberty: what's fun about all this is it's all connected, right? So the more you learn about software, the more you learn about hardware just by osmosis and vice versa, right? So I was way into like the first FPS games like Doom and Quake So you read John Carmack stuff about assembly language and optimization and that teaches you about the CPU and I just kept going reading like Anandtech Ars Technica reading that stuff and learning about it Not even thinking about it as an investment at all.

So I came to it first from a Technology and a nerd point of view and later on started learning more about these things as businesses, So curious What did you know before doing the deep dives what first made you curious about the field

MBI: Very little. don't have as cool a story as you have. was in some sense a bit fearful of semiconductors in the sense like, oh, it's too technical. Like, I'm a generalist. Like, you know, this is like kind of a more science y stuff. it would be very hard for me to catch up.

remember back in 2021, I think, in my annual letter, to my readers, I specifically mentioned semiconductors as an area, that I feel uncomfortable to do deep dives on certain companies, given the complexity and the technical jargons that are associated in all these, companies.

Liberty: few fields are as intimidating as that

MBI: Yeah, but as I kind of, you know, did it like did some deep dives and I, I think I, I realized, like, you know, this is probably more, symptoms of, like, modern, knowledge that almost, all the industries, like, we, we operate in finance, so that's why it probably feels more natural and, like, more, uh, normal, but I think, uh, for a lot of non finance people, lot of the words, a lot of the languages that we use every day and take for granted can be very, isolating.

Right. it's essentially about, you know, what you are comfortable with, what you follow, what you are interested, what you are curious about. But I think, for a long time, I just thought, yeah, you know, semiconductors, it's too technical for a generalist like me.

It will take months, if not years, to get up to speed and to understand what, this industry is about and what people are talking about. what really pushed me, to, dive deep into this industry, probably in a couple of things. The first is like, I, used to own, I still do own a lot of big tech companies.

So right now I own Meta and Amazon. I used to own Google as well. and basically for a long time, I think, you could afford to own a piece of these big tech companies without really. understanding what semiconductor is and what's the dynamics between, the broader tech industry between semiconductors, softwares and internet companies, right?

And, I think between 2022 and 2023, I started appreciating much more that I think we are getting close to a place where it's not an option You Do not understand semiconductors. uh, because you might be blindsided by the developments that's, you know, happening right now or are going to happen in the next 5 to 10 years.

just to give you a concrete example, for example, Meta. doesn't really have a pricing power. it's an auction based advertising model, right? Meta really doesn't, decide prices or impose prices.

Like, it's the auctions, right? the advertisers basically fight between themselves to decide on prices, And so that's one side of their kind of, you know, stakeholders. And the other side is basically users, right? it's a free product. So, Meta doesn't have any pricing part.

Meta basically builds advertising infrastructure. And if for some reason the advertising infrastructure becomes more and more and more expensive, They can't really pass that, extra cost to the advertisers or to users because,

Liberty: If it becomes more expensive without getting better, without the targeting getting similarly better,

MBI: right? Yeah. Yeah. If it gets better, then yes, fine.

Like, you know, maybe the auctions get tighter and tighter. It, you know, the ads become more performant. if those were the case and, you know, ROAS gets better, if those are the, reasons why advertising infrastructure's getting more expensive, then yeah, that's fine for meta.

But if it's not, if it's just, you know, the broader supply chain, some people are basically raising prices. that would be a huge concern for someone like Meta.

and obviously like, you know, Meta is spending like, billions of dollars, tens of billions of dollars these days on CapEx, they are buying chips and hand over fist from NVIDIA. So, uh, Right? So definitely jolted me, out of my comfort zone and made me realize that, this is not a reasonable excuse anymore that semiconductor is too, technical, like, you know, yes, I'm not going to be the, you know, most, expert, on semiconductors, in, in three years, five years or probably ever.

Uh, like I'm not going to be in the top 5 percentile, let's say, of semiconducting, uh, investors and experts, uh, but that's not really an excuse like from, getting your feet into understanding the basics, right? And as I kind of did that over the last 3 4 months, I realized, like, it actually gave me more comfort in, uh, in Getting into some other technical areas as well, you know, semiconductors, like it's pervasive. It's indispensable. Almost every hour, this podcast that we are recording, we're using semiconductors, right? It's everywhere. It's, literally, any person in the, in the, in the Western Hemisphere, at least, are probably using semiconductors on an hourly basis, right?

and it's not an excuse to say that, you know, oh, it's too technical. It can, everything is technical these days. simple companies like Dollar General, there are a lot of complexities in terms of the supply chain and how those things, you know, come together.

from a consumer facing, it feels like very simple. Like you just show up on the store and buy stuff, pay for that stuff. And while that seems, sounds like a very simple business. But when you realize, okay, how does the whole thing work? It becomes much more complicated, right?

So, anyways, long story short, and I think, you know, I remember in one of our, earlier episodes, I mentioned people are much more willing to say that, hey, I don't understand NVIDIA. too technical, but very few people would actually say I don't understand Meta or like Amazon or even like Google.

Like, yeah, it feels like we all understand what Google does and Facebook does and like Amazon does. But it feels socially acceptable to say I don't understand what NVIDIA does. probably we're getting closer to the point where it will be less acceptable. I don't understand what NVIDIA does, but you know, we, we know, like, if you are following, any of these big tech companies, you know, how complex and complicated even Meta or Google or, Amazon are.

because, a consumer, as a user, we see just one facets of those businesses and it feels like we get it, we understand it, that's not the case for TSMC. Like, we don't really feel like, there's a consumer element to it, right? so that's why it feels, much more technical.

Everything is like, most of the things are very technical. so if you are a generalist, and if you want to hide from, the technical aspects of different industries, different, you know, sectors. You will have a very hard time going forward. realizing that I thought I should just push myself, get into that, zone of discomfort, just be open about it.

Like, this is not my area of expertise. Just, just not, so it'll take some time. Right. So I started with like a primer, I usually do like, a company an industry, right? So I don't necessarily feel like I need to have a deep knowledge on the broader, value chain, to study a specific company, But when it comes to semiconductors, I was, I felt the opposite. I was like, okay, it feels very difficult for me to study, just TSMC or NVIDIA without understanding the broader value chain. so I was like, okay, I don't need to have very deep understanding or knowledge on the broader value chain or like every single company within the value chain.

but let's start with just lay of the land. who sits where? Who does what? Like just basic understanding what all these jargons mean and all that, right? And know, I did that first, like a general primer, then I did, like, Texas Instruments, the analog chips, then I did, like, TSMC, so the foundry business.

And I'll probably do a couple more. probably, in the digital chips, like, logic chips, uh, maybe Nvidia, maybe, some semiconductor, equipment, companies. So, probably do semiconductor, like, three to four semiconductor companies every year, for the next, like, three to five years.

I already did two so far, if I exclude primer, I feel like this industry is such a beautiful industry structure, uh, this is an industry with a very rich opportunity set, as an investor, the entire value chain has like, pockets of oligopolies, pockets of monopolies. Right? this is a industry that will Not become irrelevant. that's almost for certain for the next 10, 20, 30, even 50 years, right?

So, I will be hopefully alive in this world for the next 50 years so you know, obviously, of course, I want to gain more understanding, you know increase enhance my knowledge on an industry You That's going to be relevant for the next, you know, 50 years, right, in my lifetime.

to me, it feels like it's a very high, you know, payoff work that I'm doing. I have started doing in 2024, because I feel like in 2034, 2044, I'll, come back to this work that I did in 2024 and basically, build my knowledge on top of the kind of groundwork that I have done.

That's part of the reason why I like investing. like being a generalist because I think being a generalist allows me to understand, how the broader world works. Uh, trying to figure out putting the dots together, uh, of this, know, a gigantic map that we are kind of navigating through.

Is what makes this job incredibly fun. And I don't want to be that person who wants to avoid stuff because it's too complicated or like I, I didn't study it in college or whatever.

Liberty: Yeah. And it's not like it's a one or a zero, right? It's

even after studying this stuff for years and years, most of it. I still don't understand. Like no single person on the planet could understand every part of building a chip, right. But you can still understand a lot of what matters about the industry.

just from some higher level bits, right? So from, from understanding a a few of those things that are understandable to the generalist or the layperson, you can understand a lot of what matters without knowing every like, you know, metallurgical processes that go into making these types of transistors and how they're switching from 3D, like all that stuff, like it's cool to read about, but that's not the part that ultimately will, Make the biggest waves in the industry.

And as you say, this stuff is building blocks for every other industry. It's like software, right? It's, colonizing everything else. And so if you don't try to understand it, there's a big chance that you're going to wake up someday and find out that some industry that you, you used to understand is now like mostly like software and, buying a bunch of GPUs and AI is in there too now.

MBI: Yep. Yep. No, absolutely. And, just to put a final point on this, like, vividly remember I used to basically ignore, when I read your newsletter. And if you write anything about semiconductors, I just used to ignore it. because I don't understand it. I don't understand what you're talking about.

I'm an avid reader of your and like Ben Thompson's, you know, newsletters. And, and Ben Thompson, he also writes about semiconductors. I just used to ignore it because I don't understand it. And now that I have done, the kind of groundwork, now I do read whenever you, you or Ben Thompson or anyone else write about semiconductors.

And I understand it. I understand almost 90 percent of it. Right? again, like, you know, when you follow these things over a long period of time, your level of comfort increases, you come across semiconductors all over the world, all over, you know, everywhere you look, and you read, and you consume, and because you don't feel intimidated by it.

You don't feel like, okay, I don't understand what a fab is, right? So what's the point of reading this entire paragraph, because I don't even understand what a fab is.

Liberty: Yeah.

MBI: maybe this, podcast is all about encouraging people to actually do some work. And I'm like, I know a lot of people who get, discouraged to look at, a sector industry.

Because it's, it's a bubble, right? Or it's hot, right? Oh, like, you know, for example, like, Oh, let's say if you're in, back in 2000, Oh, there's a huge tech bubble, the internet, internet is a fad, like, not going anywhere near it. Maybe that was the right decision to be nowhere near in 2000, 2001.

But wow, what a costly decision if you just stuck to that, like, philosophy for like the last 20 years,

Liberty: Learning and investing is not the same thing too, right? it takes a little while to learn about something. So all that time invested, you'll be happy you did it if there's a crash, right? And now it's time to buy because crashes don't last forever.

And sometimes when something gets attractively priced, but if you don't know it, you start studying it. By the time you're up to speed, it's too late, right? You've missed your chance.

MBI: think we definitely, in the investment management industry, we have a fascination to only work on things or to only study things that will be worthwhile right now. Right? So let's say if you think, I'm not claiming this, but let's say if you assume the semiconductor industry is a bubble right now, then okay, what's the point of studying because it's a bubble?

Obviously I'm not going to buy stocks in a bubble like, you know, if you're a long term investor. So, no point. study it. When the crash happens, the reality is when the crash happens, when the bears will be so overjoyed and it will feel like, okay, this is a complete sham.

Like it's a fad. Like none of this was real. And even then you would feel like, what's the point of studying this industry? Like people lost their shirts. Like, you know, everybody lost money here. unless you have the, commitment to study companies or industries is.

Because you just want to understand things,

Liberty: Without the intrinsic motivation, you will never go as deep as those that actually are passionate about it, are really curious about it and will think about it in the evenings and the weekends and read books about if you're purely being a mercenary about it, like, I guess that can be fine for some things, but for more complex things, for more, for example, like, I want to go back to something you, you mentioned earlier And does apply to both what we're seeing, right? So semi conductor industry historically been very cyclical. and also, it's consolidated a bunch, a bunch of stuff has been unbundled that used to be bundled, right? You used to design chips and then fab them yourself.

And now like the fabbing has been mostly to TSMC and there's a ton of fabless companies now. So I'm curious if you think that. That has changed the industry enough that it's now less cyclical. and maybe those big opportunities that used to come every five years or whatever, where, all of a sudden you have way too much inventory.

There's so much inertia in the system. Everybody's building these fabs. It takes like, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months to build. And by the time they all come online at the same time, whoops, it's too late. Right. And the market is flooded with too many chips, too much memory, whatever, prices collapse, that stuff.

Right. That, that used to be very, very common. I feel like there's been a change in recent times. on one side, it's been consolidating. And on the other side, there's all these new end markets that use more semiconductors than before. It used to be mostly consumers or PCs or in the enterprise or whatever.

I'm curious how you feel that this thing has been changing, right? that, that's one

of biggest changes that I've been feeling in recent years.

MBI: Yeah, no, you're absolutely right. I think if you look at just the end markets, semiconductor mix, so PCs and consumer electronics, even today, it's still like 55, 56 percent of, total, you know, semiconductor chips, there are like, you know, industrial, automotive, and there's something else.

They're each like 14%. of the total in markets, uh, mix. so still like, you know, low compared to, PCs and consumer electronics. But those three are like the more, high growth. PCs and, you know, consumer electronics are kind of flat lining, are barely growing, But, those other three are definitely growing a lot faster. so for example, like, you give Texas Instruments example, Their revenue basically grew at less than 4 percent over the last like 10 years, right? but if you look at their only industrial and automotive,

Liberty: Yeah. The mix under the, surface has been changing a lot.

MBI: Yeah, so back in 2013, industrial and automotive used to be like 40 percent of Texas Instruments, revenue.

Today it's 75%. And if you just look at how industrials and automotive grew over the last 10 years, industrial grew at like 9 10 percent automotive grew at like 14 15 percent CAGR. Even though the top line, appears to have grown only at 3. 7 or something like a percent CAGR.

again, this development is, to your point, beneficial, from, these chips companies perspective because, consumer electronics, PCs, they used to be very short cycle, products. more challenging to foresee demands and how, and the volatility of demand, was definitely higher, which makes, you know, kind of the bullwhip effect that happens, when it comes to that, because, some of these companies, semiconductor chips companies Don't really have a direct, uh, way to track demand.

Like, let's say Apple can track how iPhones are selling the companies who are basically, manufacturing chips for a apple, have like, you know, kind of a converted window, to track that. but industrials, automotive.

These are more high growth, and these are very long design cycle. So once, you know, a chip is in in an automotive or in, in a factory, design, they tend to last lot longer than a smartphone

chip

Liberty: especially the kinds of chips that Texas Instruments makes. Right. in all these things, there's some chips that you wanna be on the cutting edge. You want the fast thing. If it's The, the screen on the car, right? The infotainment and all that. But if it's like a sensor for like a, a window or a temperature sensor, all that stuff's like, once it works, it can stick around for decades sometimes.

MBI: Yeah, I, I think, ADI, Analog Devices, uh, mentions, explicitly that 50 percent of their revenue comes from chips that were, on an average a decade old, right? and obviously like you have already kind of done your R&D on, on those, chips and you, you know how to manufacture them.

So, you know, the margins can be really lucrative. Like one thing that I mentioned, like, you know, like when we imagine a cyclical industry or cyclical company, basically imagine what, like, you know, their top lines are going up and down, their, operating profits are going like up and down, margins are kind of, you know, Compressing a lot or maybe even losing money and then on the upcycle, they're making a lot of money.

That's true That's still true for memory companies, right? So like microns of the world, right? Uh, but for a lot of the companies like, text instruments TSMC, right? Are they cyclical? Yes, Texas Instruments. I think revenue was down You nine, 10 percent in like 2021 and 2023, I think, like, even in 2000, for example, when the tech bubble crashed, uh, Texas Instruments top line was down like 30%, and like during GFC, global financial crisis, their revenue declined in three consecutive years.

So obviously this is a cyclical company, cyclical industry, but I think what people miss that because of the industry structure, because of where these companies position themselves or have positioned themselves over time, in the broader value chain. Their margins are actually a lot less cyclical.

Like, for Texas Instruments, even during down cycle, like Last five years, they had a couple of years where the revenue declined by 10 to 12 percent. And they still had operating margin of 40 percent. Like, where, how many companies can you find in the world Where you would have 10 percent decline in revenue and still have like 40 percent operating margin, right?

And obviously in the upcycle, they have like, you know, 50 percent operating margin, right? So there's obviously a difference between their performance in like downcycle and upcycle. But the difference, like, is you're talking about, are you, are you going to post 40 percent operating margin or 50 percent or 60 percent operating margin? Those two seem like pretty good option, right? So I'm not claiming these are not cyclical companies. These are cyclical companies, but I think people kind of, you know, stretch that logic kind of broad brush all cyclical companies together. But know, you have to take into account the industry structure here.

Right? not like because it's a down cycle, there's a flood of like, you know, chips coming in and they're just, you know, selling it for, for, cents, and losing money during the down cycle, right? That's not what's happening even for TSMC exceptionally, high CapEx business.

So very, you know, operational leveraged business. depreciation expense is basically 30 50 percent of their revenue, right? if their revenue kind of goes down in a down cycle, obviously, like, the depreciation expense is kind of fixed, right? you're just, you know, uh, dividing it over the course of the useful life.

So, so yes, margins can compress, but again, even for TSMC, Since 2003, so almost it's been like 20 years, I think they have always maintained at least 30 percent operating margin. I have studied, you know, many, many companies so far. Like, you know, even for MBI Deep Dives, I did like 48 deep dives so far.

And it's exceptionally rare for 30 percent margin in like any normal year, right? And we're talking about down cycle, like, revenues going down 10%, 15%, right? And still, these companies are being able to post 40, 30, 40, 50 percent margin, right? So, I, think, people should, contextualize the cyclicality, of this industry a bit more.

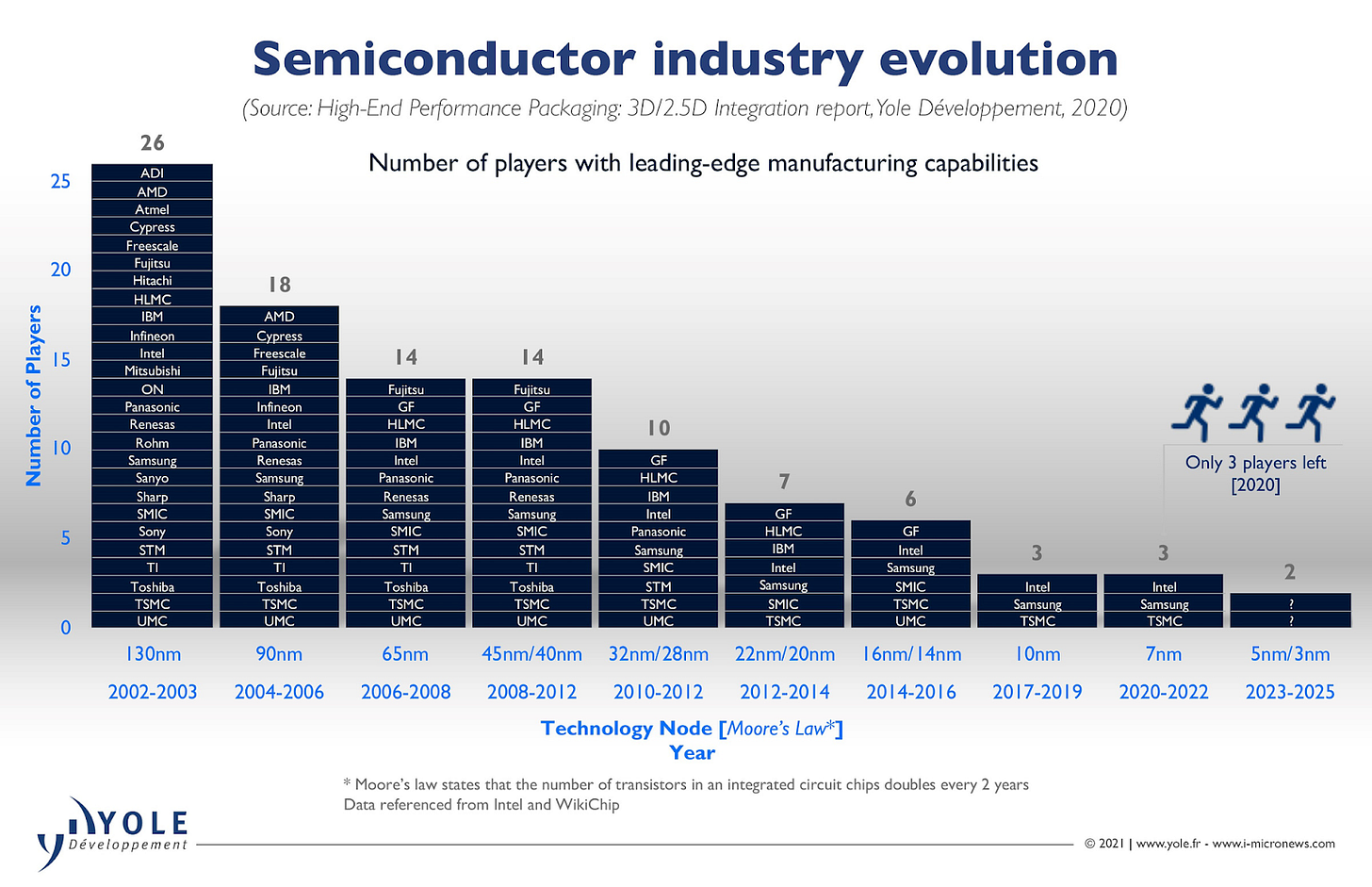

if I have to, think from the investor's perspective, who think it's the cyclical nature of the industry too much, the industry structure wasn't always like this, right? So, in the early 2000s, for example, there were Almost 30 companies in the leading edge chip manufacturing, right?

Today it's effectively one,

right? It's a TSMC, right?

Liberty: 5 maybe. Some, once in a

MBI: yeah. yeah. yeah. So yeah, we talk about Samsung and Intel, right? But like for all intents and purposes, if you want to do like, you know, to manufacture chips at, at the, in the 3 nanometer, It's essentially just TSMC, right? It's, it's

Liberty: Yeah, and all that capacity is bought up by Apple.

and Nvidia pretty much like whoever has the highest margin on

Is able to lock up most of the first round of the leading node right now. love how you mentioned how whole industry is basically a bunch of monopolies and duopolies, which sounds great at first, but then like someone told you, like, yeah, but if they're all monopolies or duopolies, like how much leverage do they have over each other?

And so it's a very interesting dynamic can't think really of another industry where there are so many players. But they're all at this point, solid in their slice of the value chain. from one end to the other, right? there's the people making the picks and shovels on one side, like ASML, Applied Materials, LAM.

there's the software player with synopsis and all pretty much have their niche locked up, which wasn't the case years ago. Like there's a great graph in one of your deep dives where you see the number of, of fabs from different companies. And it's basically like a, Descending staircase, right?

It's like, Oh, there used to be like 30 different companies having fabbing chips. at the leaning edge and now the leaning edge is basically just TSMC. And so for some of the players where chips obsolete very quickly, right? So if you're making a leading edge, like very sexy logic chip or, very fast memory or something, and there's a down cycle and you can't sell it, well, two, three years later, like, The leading edge is advanced.

The technology is better. Your chips are not competitive anymore. And so that could be a huge loss, but for. TSMC where there's basically nowhere else to go to fab leading edge. Customers will come back to you, right? You don't have to do much. And if you're Texas Instruments or ADI, you pile up the chips in a warehouse and you sell them later because they have like a decade long shelf life.

there's not something else that comes and obsolete them, right? So understanding these differences between the different players in the value chains and finding those that. basically fit what you're looking for to bet on in the industry. If you think like we're just at the beginning of this huge wave with AI and whatever, and like, maybe the sexiest companies are the ones that are going to make the most money, right?

Nvidia and all that, like with like almost 60 percent free cash flow margins right now. Like who knows if that keeps going up, but if that changes, going to be maybe hit harder by the cycle than someone like, Texas Instrument that didn't, Participate as much in the upside, but just keeps chugging along, doing stuff, like building more 300 millimeter fabs for later when maybe something happens with China.

And there's no more like every one of these companies has like its own personality, which is, I don't know. I find it very fun to study.

MBI: Yeah, no, absolutely. I think, you know, to your point about, series of, duopolies or oligopolies in, like, different, parts of the entire value chain. Like, in just, I think, a few couple of days ago, Jensen Huang, I think, uh, NVIDIA CEO mentioned, TSMC should raise price. Like, where would you find, like, that you're, you know, the customer is saying I would love to, I, I'm okay with paying higher prices.

for the chips I'm buying, the reason he's saying that because he's so comfortable, about his position in the, value chain and, I think the power that he possesses to just pass that cost increases to their customers,

Liberty: Yeah. But also it's making it harder for competitors To get fabbing time on TSMC if the prices higher, right? So it's kind of like a Also building a moat around the most profitable players

But that's one of the questions about TSMC like they recently had I think a CEO change or chairman change they recently changed and one of the theories were that they didn't, Press on their advantage with pricing they've been basically a monopoly at the leading edge for years now But they've kept pricing their chips You Similarly, so all of the value went to Apple and Nvidia and others.

And, and don't get me wrong, the SMC still had very nice returns on capital and margins, but they could have done so much more, That's always one of the questions, like when you become basically a monopoly, like they are how far do you go? And if you do go too far, does that causes you to become like fatter and lazier?

And does that create a pricing umbrella under which others could come under maybe? But how long does that take? Like, it's so, it's so hard to figure out, like, what's optimal strategy there for

MBI: Yeah, I think, you know, uh, to TSMC's management, you know, defense, if I have to defend them, but, the reality is, I think it's not like they have been, in this monopoly status for too long, right? So they were kind of behind for a long time, the company was founded in 1987, like, Intel wasn't like in 1960s.

Uh, and Intel was ahead for a long time and then up until like in the mid 2010s. Right. So like in 2015, 2016, something like somewhere around that, where basically Intel started falling behind. So TSMC had to, take that lead. But you couldn't be really certain that that's going to be the equilibrium state for forever, right?

So they had to exceed them. They had to kind of, you know, make sure that they are there, they are at the leading edge and again, Samsung was also falling behind in the in more recent years. So it's more of a recent phenomenon the kind of monopoly that TSMC

Liberty: Oh yeah. It's definitely made surely the past five years.

Maybe in the past 10 years, there could be signs of it. And there's a kind of network effect where the more customers TSMC has, the more, money they have for R& D and CapEx. And so all customers benefit from it, right? There's this kind of effect where Intel or anybody that's fully vertically integrated doesn't get.

And so as soon as Intel has trouble, like a, uh, vicious cycle where, okay, you're losing profit and revenue by selling fewer chips. And by selling fewer chips, you have less to invest in fabs and R& D and CapEx to keep up with TSMC.

MBI: Yeah, no, I mean, TSMC used to have low 40s gross margin in, like, 2000s and then in 2010s they had, high 40s gross margin. And in this decade so far, they are at like mid 50s gross margin. So if you think like gross margin is improving, so they are clearly, you know, obviously, the price, uh, at a premium, point for the leading edge chips, right?

and they did raise prices, but again, the, the question is, that given that their customers like Nvidia, for example, are having like 70%, you know, gross margin or even higher. Right. so there's a question like, you know,

did they,

Liberty: Are they capturing their fair share of the value they're creating? Because at this point, if suddenly TSMC disappeared, right, how much value would disappear for all of these other companies?

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: I love your title. The most mission critical company on earth, right?

MBI: Yeah,

Liberty: we start talking about like problems with China and Taiwan and geopolitics, or if that didn't exist, they would be a lot more comfortable. Let's say, but, but maybe that's something to talk about now. Right. Cause that's another question. It's like when you start learning about TSMC on the technical side, it's hard not to fall in love because like what they've built is amazing.

It's some of humanity's most impressive technical achievements. And like, it's almost like magic, right? It's, it's really, really cool.

MBI: Yeah. I

mean, just to put it in context, right?

I'm not a very religious person. You But it almost, you know, like when you, when you, you know, when you read this semiconductor stuff, like, Oh my god, my fellow human beings Came up with all this stuff, right? Like I'm in the same species Right. So it's truly incredible.

Like it's, unbelievably humbling and the fact that like, you know, obviously, semiconductors like, you know, silicon is the second most abundant element in the world right after oxygen, how lucky we are in sense that, silicons are so abundant, that lets us basically, you know, use semiconductors to improve our, life, and society and, technological progress in itself. so yeah, like, and when you think in like those terms in a more kind of, you know, deeper way, there is a sense of spirituality here.

Liberty: My favorite way of putting it is that, you know, when you combine that with AI, it's like, we've got thinking sand at this point.

MBI: love that. I really love that characterization. Yeah, thinking sand, you know? Yeah, like, you know, when you think in those terms, obviously we think about these things in more of an inanimate objects. think I saw like, Instagram reels, how CPU is, made. how could we come up with this? It's absurd, the fact that human beings came up with this, or thought about this, that this is even possible, It's incredible to me.

Liberty: It's also a great example of the power of incremental improvement because you

could never go from nothing to what we have today. But when you read about like Bell Labs and the first transistors, they were kind of handmade, right? And you would hand wire them together and everything was at a macro scale, very different from today.

But then year by year you shrink everything, you optimize everything, you change everything, and you fix one problem at a time with like photolithography and this and all of those steps together over all those years leads you to here. It's a bit similar to evolution, like evolve the eye, right?

The first is like a cell on the surface of skin that detects darkness and light. That's it. And then stuff changes around it, right? It goes recessed a little bit, so you can get like some directionality to shadows and then this, and then that, and over millions and millions of years, you have the eye, right?

Thankfully humans work faster than evolution, but it's a similar process of incremental improvement

fixing one problem at a time.

MBI: if you think about it, just in Morris Chang's lifetime, like when he was born,

Liberty: Hmm.

MBI: industry wasn't like, the word semiconductor probably wasn't in the lexicon, right?

Right. 55. mentioned this on my deep dive, but I am absolutely shocked that there hasn't been a movie made on his life.

I think, This guy probably deserves a movie, and I hope they do a bit of a justice to his life, because he had two separate careers. He spent 30 years, nearly 30 years, in Texas Instruments, right? And then he, started TSMC at age 55, and then he ran it for a couple of decades, and then he retired.

Then he came back and doubled down on CapEx spree, in like, in the middle of, global financial crisis when everyone was kind of, you know, reeling. And he was like, no, we are going to go all out and we are going to spend a lot more on CapEx. This is a moment to, uh, aggressive and capture market share and be on the forefront of, technology, right?

it's just unbelievable story and the more I studied his life read about his life, you know, he's still alive. So when he was born in like 1930s, like I was saying, like, you know, semiconductor was probably not part of the lexicon,

Liberty: the transistor wasn't even

invented.

MBI: Chang joined, Texas Instruments in 1958. So these are, in some sense, a very young industry. It's not like, you know, 400 years ago, these things were invented and we were getting you mentioned about incremental improvement and that's true, but the pace of incremental improvement has been

Liberty: Oh, it's compounding. Yeah,

it's, it's, Moore's law incredible. And, what you say about Mars Chang, right? It's another notch in the, like, great man theory of history, because, cause I think he wasn't running to be CEO of Texas Instruments at the time. He didn't get it. And that's one of the reasons why he went back to Taiwan and started TSMC.

what if he had been TI's CEO?

maybe the whole world would be different today, right? Taiwan probably would not be specialized in this because they had, they had no natural advantages there. It was like force of will that kind of built TSMC and other semi companies in Taiwan didn't do nearly as well, right?

And now there's an ecosystem, there's talent, it's different. But if you look at early years, like, really made a huge difference there. As I said, like you kind of fall in love, but then you, you started looking at like the situation with China and, that makes it, I don't know.

That makes me very nervous, right? Not only for TSMC, but for, as we said, it's the most mission critical company on earth. And so. If there's a problem with them,

like who doesn't have a problem, right?

And I'm kind of curious what you think about the whole export controls on China. clearly there's tons of smuggling There's all these third party countries that all of a sudden become like some of nvidia's biggest customers Some of those ships probably end up there and there's always been but there's industrial espionage, right?

It's a lot easier to copy something than to come up with it. So don't know how much difference You All that is making, but I do know that while TSMC as long as they're clearly in the lead, there's what they call the silicon shield that kind of protects Taiwan, right? That makes them so mission critical that, US or whoever will want to defend them or at least do more to, deter, China.

But now that everybody's pressuring TSMC to build fabs elsewhere, like in Arizona and Japan and Is that a kind of Catch 22 where you think you're diversifying and reducing risk, but you're actually increasing risk or

we can't know, obviously, but I'm

MBI: yeah.

Liberty: you think about this huge, sword of Damocles.

MBI: There's definitely a bit of a catch 22 there, yes, like, you know, after I did my primer, one of my conclusions was initially that, China is unlikely to invade Taiwan, anytime soon. I think, you know, as I kind of thought more and more about it, I kind of, you know, probably would like to rephrase it in a different way.

So I don't expect China to invade Taiwan. for the purpose of, let's say, acquiring TSMC's technology or IP,

Liberty: I don't, think that everything is so fragile there. And so much is dependent on tacit knowledge in the

MBI: Right.

Liberty: that you can't acquire that at the point of a gun.

MBI: So, but the thing is, life is not only about technology or TSMC or, there are many different facets of, China, you know,

Liberty: rational.

MBI: Exactly. so yeah, it doesn't have to be rational, so I think when I wrote that, one of my conclusions after being the primer, I think I was probably thinking more rationally, I think I may have missed the perspective that not everyone has

to be

rational.

Liberty: it shouldn't happen, but

MBI: Right.

Liberty: still. And it could

be lose lose. Everybody could lose from it and it would still happen.

MBI: Exactly. Right. Like, you know, thinking like, oh, Let's invade Taiwan. Then we can have No, I think that they understand they're not going to have TSMC even if they invade Taiwan or like, have independence. on semiconductor value chain, even if Taiwan, but they may have other reasons to invade Taiwan.

Liberty: it could be to deny TSMC to the rest of the world, right? Maybe it hurts the rest of the world more than it hurts China. And they've been working very hard to try to build up their homegrown semiconductor industry. That's been very hard. They're pretty behind, but in 10 years, where, where will they be?

I don't know. Right.

MBI: Yeah, so, I mean, think the risk is very tangible. I think the risk is very real. to put this in, kind of, in a perspective or context, If you ask me, okay, is China going to invade Taiwan next year? I don't know. Nobody knows, right? Five years, ten years, nobody knows.

But when I ask myself, if I come back to the world 500 years from now, would I see Taiwan as part of China or no? I think it's significantly more likely that this, invasion is it almost feels inevitable at some

Liberty: 500 is hard because 500, like the U. S. didn't even exist 500, like China may not even be communist by then, who knows, but a hundred years or 50 years, that, I could see more, as possible

MBI: even

50

seems, feels like it's more likely than not that an invasion will happen. again, to your point, not going to be like, you know, a huge benefit. Uh, you know, China is not going to be a beneficiary. from technological perspective, through this invasion, it's unlikely, but yeah, it's, it's definitely going to hurt, everyone else, and they may not be in the mood of, calculating is hurt more or less. Maybe the point is everybody gets hurt and everybody has to go to the drawing board to kind of rebuild, so many things from, from ground zero. And yeah, like, you know, when I really think about these things, I come back to, what my grandfather had to go through.

So my grandfather basically never really moved from his village in Bangladesh, but in his entire life, the name of his country changed three times.

Liberty: Hmm.

MBI: Right? you know, when he was born, Bangladesh was part of the British Empire, right? Then, late 1940s, it was Pakistan, Then in 1971, it became Bangladesh, But he never really moved at all from his village, right?

Liberty: Yeah. Or even just like my grandmother lived on the farm without electricity or running water

MBI: yeah, exactly.

Liberty: Right. It's, it's, it's a huge change for not that long.

MBI: Not that long, right, exactly. So, we, we definitely have to entertain the possibility that in our lifetime, we will experience some, uh, Incredibly volatile periods. that's not a very exceptionally low probability event either, right? a real risk, for not only TSMC but also for, almost any tech company.

Liberty: that's one thing you wrote about that, that like,

All of the big tech were actually more fragile than they seem because all the hyperscalers, both as, hyperscalers reselling that stuff to others, but also for their own use, right?

Like Google is using how much semiconductor, right? Like, so it's very hard to, Place bets on that type of stuff, like, okay. Buying TSMC or not feels like a more direct bet on that, but

MBI: yeah. No,

Liberty: buying Google is kind of also a bet on that.

MBI: no, no, absolutely. totally agree. It's a, highly correlated bet. I feel like if you own any stock, will be some correlation, but yeah, it's a very highly correlated bet. But I think the only distinction that I would draw between TSMCs and like the big techs of the U. S. is I think if China invades Taiwan, I think Taiwan's stock goes down by 80, 90 or even 100 percent, who knows, and it never comes back.

just never comes back to what, it's worth today, right?

Liberty: Yeah. Well, I wouldn't say the same for Google or

MBI: Right. So yes, absolutely. Like, you know, all these big U. S. like magnificent seven stocks, they will all be down somewhere between 30 to 70%, let's say. it'll take like years. It'll probably take like three to six months or something like that, right?

So there will be incredible pain point, I think, for anyone who owns any of the stocks. but I think, Yes, like over time, as we kind of rebuilt, the entire process, I think, you know, yeah, it will take years, maybe even decades, but, these companies, you know, if they have their core business intact, it's certainly possible that they will recoup lost value and it may not be a permanent capital.

impairment like TSMCs would be. So that's the difference of risk that I see. it's going to be incredibly painful for anyone who owns any, any tech companies that I mentioned. but yeah, for TSMCs, I think it's likely to be permanent capital impairment even if TSMCs exists, you know, maybe they will need, more capital infusion.

The shareholder structure, the capital structure may have to change, they're not really a, a leveraged company or anything like that, but it's going to be a shell of a company then, compared to what they are today, even if they recoup that value, it will take significantly longer than any of these U.

S. big tech

Liberty: yeah.

let's move on to something less depressing. Well, of the other interesting aspects that I, I've been keeping track of, in the industry is how, like, every scaled Player. The, the hyperscalers basically are all kind of turning into chip designers themselves over time. So they used to be like Intel and AMD in logic and NVIDIA came on and pioneered a lot of the GPU stuff.

And then ATI followed, AMD bought ATI and okay, that's a thing. Their There's memory over there. There's all these players, right? But now we have players that are, that have basically grown up doing other things and now like Apple is designing its own chip very successfully.

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: putting them in all of their own product, buying less stuff from everybody else.

Microsoft, Google, AWS, they're all designing all kinds of chips for, a bunch of arm chips now taking over a lot of server stuff, uh, from, the x86 people. it feels like a big, big industry change. And I wonder what the, the mature state is over there, right? is going to squeeze out?

Players like, AMD and Intel, It's always hard to know. Cause a lot of it depends on all these cycles, right? So there used to be like the PC cycle, everybody rode in the mobile cycle. And now it's AI. How long does that have to go?

Is there a next one after that? Is someone else going to be the, kind of Perfectly, tuned the player to benefit from it. I don't know, but it feels like that's one of the big undercurrents right now.

MBI: anything that can be solved by capital, I think the US big tech companies will definitely take a shot at that, right? If it's not about capital, it's about something else, then that's where things can become problematic. Like, you know, for example, the chip manufacturing, like what TSMC is doing, it's not like, Apple can just wake up tomorrow and say, you know what, let's just take out.

20 billion and build a fab like in the US, right? They have 100 billion dollar cash lying in their balance sheet, right? So they can do that theoretically, but that's not how it works,

right? Exactly, right, exactly. So, you know, I have this kind of wild theory. I feel Intel's, fab division, I wish they, that were spun off, right. And, I wish that took investment from this magnificent seven companies,

right.

Liberty: of cartel to diversify away from TSMC.

MBI: I mean, they, not only those seven companies will be the biggest losers if something happens to TSMC, all of American people will be losers too, but they will be the biggest losers.

So, for example, when U. S. government is giving, like, subsidies to Intel, right, All of us are chipping in, entire tax base is chipping in, but who is going to be the biggest beneficiary if, Intel is successful? Obviously Intel is going to be beneficiary, but then the second order of effects is like these seven companies, right?

And I feel like they should probably take more, risk in that context, right? they have a lot of capital, you know,

Liberty: like that. everybody chipped in like five or 10 billion, that would be a gigantic amount. I think the bottleneck would clearly be other things like, talent and, all that type of

stuff, or just getting through like

NEPA and all the regulations in the U S to build anything. But that could be like in, in a crisis that

MBI: yeah,

Liberty: streamlined.

MBI: it's a lot harder to attract talent, like high quality talent to Intel at this point, right? versus like if you were just spun off to a new kind of startup, so like new equity value and like all that, like you have like new stock

Liberty: Yeah. And focus.

MBI: And focus.

this is your job.

Liberty: Maybe even combine it with global foundries, like

MBI: Yes, whatever. Yeah.

Liberty: but they have the customer service type of, of

MBI: right, right.

Liberty: doesn't have. Cause they haven't been dealing with third parties so far.

MBI: it's essentially financed by like a consortium of this magnificent seven. Because I feel like, you know, as a shareholder of Amazon and Meta, I feel like it's almost like, you know, if I were Mark Zuckerberg, it would feel like an unacceptable risk that we are kind of, you know, underwriting here.

pretty sure Jeff Bezos and, Sundar Pichai and like Satya Nadella are not a huge fan of having such a glaring risk you are like, you know, tiny shareholders of some of these companies, and even we feel uncomfortable when you think about this risk, like imagine, you know, what these people, must feel, when they think about this kind of, you know, tail events.

it may happen. Who knows? Maybe, Intel, is unsuccessful in having like, high yield or like, you know, getting, you know, enough customers and maybe it will fail and

who

knows?

Liberty: imagine an inverted pyramid where like there's

TSMC at the bottom and

whatever

market cap they have right now. I haven't looked recently, but some hundreds of billions.

MBI: 700 to 900 billion dollars. Yeah.

Liberty: How much, value is resting on that? say Like, let's take all of the big texts, like multiple, multiple trillions, then look at everything that's national security, right?

Like clearly if the US had its own leading fabs all kinds of military applications like satellite telecoms, all kinds of stuff would be fab there for security reasons.

And that would be part of like, in the same way that in the early days of, semiconductors, a lot of the early contracts came from the government, right?

Military, nasa. spy stuff, CIA, all kinds of stuff helped basically finance the early days and get them to scale. It would be kind of that new moment for regrowing that industry. could totally see that because as I said, right, if there's like, I don't know, 10 trillion of market cap

resting on this one company could go away,

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: wouldn't be too expensive as insurance to spend like a

MBI: Oh, it's nothing.

When you think in those terms, like the potential market cap lost. And again, it's not just these five, seven companies. going to be a recession, like deep, deep

Liberty: No, no. Worldwide. Yeah.

Yeah,

MBI: Yeah, people are going to lose jobs left and right, like, you know, real estate prices will, like, everything will be affected, right?

Liberty: Noticeable quality of life stuff, right? It's almost like, uh, okay. That sounds a bit hyperbolic, but you know how like human progress kind of slowed down and stopped and even went back in the middle ages compared to antiquity or something, I could see how there's all these curves on log charts where everything is going better.

Like number of transistors, speed of stuff, like AI, everything is going better. And if something happened to TSMC, you would see it in the chart, in the log chart, you

MBI: absolutely.

Liberty: a big bump, right. And, and trying to prevent that has a, net present value that's in the

MBI: it's, it's nothing, like, 10, 10 billion dollars, all, every single of this, like, you know, big tech companies have at least 10 billion dollar cash, net cash, not even, like, you know, net cash on their balance sheet. you know, and again, like in most of the cases, they're just getting interest on that cash.

So if you can solve a tail event, with the opportunity cost of like four or 5 percent of yield that you are making, to me, that's a no brainer, but maybe it's not politically, not palatable,

Liberty: it's probably a coordination problem too, right?

MBI: Yeah, could be.

MBI: Like, you need to see a realistic attempt by China, I think.

Like, you know, feels very imminent, like it feels like, you know, almost happening. Or maybe it's, like, you know, once it starts, then things will kind of, you know, come into

Liberty: Yeah, that's kind of too

late.

MBI: that's too late. Yeah, I know. It

Liberty: And there's the catch 22 too, that even if they start now and they make great progress, is that sending a signal to China that they should act sooner rather than later? Right. You may, you may almost like create the event and it would maybe have happened anyway.

MBI: Could you, could you elaborate that?

Liberty: Oh, I just mean that right now there's a kind of silicon shield protecting Taiwan. So if China attacks, like everybody gets hurt a lot. If the US builds up like another homegrown TSMC, USMC or whatever. Right. And it works and it can fab like leading edge stuff. Is all of a sudden like Taiwan on its own because people won't go to its defense and so China's like well Now's the time to go

MBI: I think if China wants to invade Taiwan, it's not necessarily going to be because of TSMC. It's like they actually want Taiwan to be part of their country. So if that's the case, then, like, that's what I'm saying. I think invasion is going to happen, like, whether TSMC exists or not, right?

like even if, for example, TSMC, were not part of Taiwan, like it's completely in the US, yeah, if you are a Taiwanese, that's a very bad news. that means we have accelerated that invasion timeline

Liberty: yeah,

MBI: timeline. but for the rest of the world, it's probably less of a bad news. I know

it's a very, putting it very crudely and, it's

definitely politically,

Liberty: no great choice right it's

MBI: great choice, not not a great choice. yeah, we have basically an option where, all the country in the world basically more or less gets hurt, versus, Another situation where, Taiwanese people get hurt, right? So it's not great to have those two options, but unfortunately that's the one we are dealing with.

Liberty: love to talk a bit more about Texas Instruments because I think it's a little very interesting company that has so much history, right? It's like the OG in the industry. Uh, like mentioned our Morris Chang came from there, but like, yeah, they, they invented the integrated circuit there.

Um, the transistor was invented at Bell labs, but it was kind of

perfected at Texas instrument, largely the thought that They have all their own fabs. Now they're moving their fabs from 200 millimeter to 300 millimeter wafers, which gives them like, you better gross margins and better economics.

They're doing all kinds of interesting things. what stands out to me a lot is how, as capital allocators, how transparent they are and how clear they are. And they have these, like call where they talk about just capital allocation, basically. It's like by segment, it's like, we're going to reinvest more R& D here and the returns there.

And. I kind of wish every company was that clear. I don't know how you feel studying text instruments. How do you feel about that aspect of them?

MBI: Yeah, before that, I just want to, clarify. I think I mentioned before that, in 1958, transistor was, uh, invented in Texas Instruments. Actually, that's integrated circuit IC chip by Jack Kilby. but yeah, like, you they have a, like, a separate capital allocation deck, like, presentation that they do every year with, investors, right?

With, you know, analysts. just wish I could send that presentation to every single company that I, you know, personally own, just to see how to communicate, with investors and the clarity of thinking. it's so. Pathetic that so many of tech companies still think about, buying back shares to offset dilution.

Liberty: Yes.

MBI: I don't know, like these are exceptionally highly paid executives and if they make a basic math mistake, right? I, I actually don't understand why analysts even don't push back against that. Like they just, Take it, you know, like it's fine, like it's, right or rational.

It's not, right? So, but yeah, like, you know, Texas Instruments have incredible clarity in terms of communication, and have a very systematic way of thinking about capital allocation. Like, they are not, buying back shares to offset dilution, right? They are not buying back shares for the sake of it like, you know, they came to be more opportunistic like, you know, I think last 20 years they generated like 100 billion dollars of Operating cash flow.

5 billion of that was spent on stock based compensation. 25 billion was like capital expenditures. And the rest was basically returned to shareholders through, through buyback and dividends. Right. what I really liked about like, you know, I think efficiency, like I know Mark Zuckerberg talks about efficiency in like 2023.

he found religion on that. it's unfortunate that he had to find religion after, like, you know, the stock was decimated. I feel like it should be the, you know, normal course of operation of a business, right? and that's what you see, when it comes to Texas Instruments.

in, like, 10 years, like, 2013 to 2023, their gross profit increased by, like, 5 billion. over that period and their, operating expense was almost flat. I don't think I've ever seen that.

Liberty: Yeah. That.

MBI: can you grow your gross profit by 5 billion without raising any, like, operating expense over an entire decade,

right?

Liberty: right? It's not like a software company

MBI: No.

Liberty: like print bits.

MBI: No, absolutely not, right? So, and it's possible only if you take great care of how you are, allocating capital. So, for example, like I was saying, their automotive and industrial segments was growing like at, like almost low double digit CAGR during that period. And they were investing in R& D in those particular segments.

But then there's, that's that used to be like 40%. So, like. The 60 percent of the revenue that they had in 2013 was more like very slow growth or even in some cases declining. And they weren't really spending much R& D there,

Liberty: reminds me of constellation a bit where some business units inside of the company may be like runoffs or just milk for cash. Others that are getting great returns or organic growth are being invested in. And so if you look at just the aggregate, the top line, it's easy to lose track of what's going on underneath and what's creating more value, right?

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: you look at, the margins are moving, that's where you see like, okay, like something is happening. It's not the same mix underneath.

MBI: Yeah. Yeah. And frankly speaking, this is partly why I was kind of surprised that the activist investor

in Elliott came after Texas Instruments. I was like There are so many companies in the market right now, especially tech companies, who would probably get benefited with some activism, right?

With, some activist investors coming into the board, but Texas Instrument feels like, you know, at the bottom of that pile, where management needs some activist shareholders to tell them what to do. I think they take great care, the way they communicate, the way they, even like, you know, read the very first, two pages of their 10k, you'll get the sense, like what they're about, how they think and how, they think about capital allocation.

how they think about efficiency how they operate for long term investors, right? Who cares? Like, you know, the hedge fund is losing some money in the next quarter or two, right? and obviously like I said, this is cyclical industry. You can't really know What 2026, 2027 revenue is going to be, Because that depends on the cycle. It depends on the economy. That depends on the inventory cycle that you will be on, right? And, for them to manage the business, assuming what the top line is going to be in 2026, 2027, rather they know This is a secular industry, like, you know, like I said, chips will be around and the product they sell, it's not like, they're selling groceries that if they don't sell tomorrow, going to be rotten and, it's going to be sunk cost, right?

That's not the case. So they will be able to sell these chips later when the demand comes back and the demand will come back because of the kind of industry that they operate in. So The only risk that I see, it's not that, like, you know, they are spending on CapEx, but they are spending on CapEx because of the CHIPS Act, right, because of the subsidies and the tax credit that they are receiving from the government.

And there is a timeline associated with that. So it's not like, you know, they can just choose to delay it, at some future time. the risk is definitely, in some sense associated with China again. because China is also trying to, be more, reliant on homegrown, companies and, don't have as much, you know, general purpose, like, you know, broad suite of, uh, SKUs like Texas Instruments does, but they tend to be more aggressive in terms of pricing, but, their product portfolio is more limited, and, But it's a government mandate, for example, like, hey, if there's like two alternatives, one from Texas Instruments and one from, this Chinese company, you have to choose the Chinese company. Like, you know, something like that doesn't even have to be explicit. It can be just a nudge from the government, right?

and in China, it's 20 percent of revenue for Texas Instruments. So, so that's definitely a source of potential, risk for them.

Liberty: I thought the letter from Elliot was very unique in that it's an activist letter and usually when you read those it's like The sky is falling, right? Basically, listen to me or everything's going down.

And this one was like praising Texas Instruments for pages and pages.

And basically then it's like, Oh, by the way, we'd like you to kind of modulate and be more flexible on capex, right?

But everything is great.

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: from that, it was, it was very interesting.

MBI: a good letter. they're not like trying to, sound too short termist, but at the same time, I feel like, you know, just get to one point they mentioned. like, oh, consensus 2026 revenue is this, and like, who knows what's

2026 revenue?

Like,

Liberty: always over extrapolate the present, right? So

when it was going great, everybody expected it to keep going. And now it's slowing down and everybody's.

MBI: they mention, like, you know, like, consensus estimate used to be this, and now this. Like, if consensus estimates can be wrong, like, a couple of years ago, why can't they be wrong again in, like, today, right? So, for a company to rely on what's the consensus estimates is, and take any decision, not just this type of decision, any decision based on consensus estimates is two, three years out, to me is fallacious.

And at the same time, they did mention in their letter that what they're suggesting will still allow Texas Instruments to enjoy the tax credits from the CHIPS Act, but they didn't really elaborate on that. Like, I wasn't really sure I understand. Why or how? Because, at least the way Texas Instruments, uh, describes or explains, it feels like very time bound.

And even, I mean, even the Chips, you know, Act people also explains it that way. So it's not like, and they have to promise a certain thing, like, you know, I, I listened to, uh, some podcasts on Chips Act, from people who are, taking these decisions, for the CHIPS act.

And I think they clearly mentioned like they, are trying to contribute like 15 percent of the total, investment that the company is making, right? So imagine like the government is giving you 5 to 15 percent of the total, you know, investment and you are saying after like a few quarters, like, hey, my consensus estimates are down.

So I'm not going to through it, or I'm going to delay it, then you'll be in the, probably in the black box,

Liberty: Yeah.

MBI: the government.

Liberty: Texas Instruments has a long history of being bargain hunters and contrarians and investing during down cycles and while others don't want to. Right. And that never feels great at the time.

But it usually turns out in the longterm to have been the thing to do. Right. I think it was in the, the GFC that they bought a bunch of like used instruments and like, they filled basically fabs with, equipment that they bought for like pennies on the dollar.

Right. And that turned out to be great. They do M& A once in a while. Most of the time they get pretty good prices. I think it's been going up a bit over time, but they don't do a ton of M& A. I think, uh, analog devices has been doing more of it, but generally I would tend to trust them to know their business very well in this case.

And to. Probably be thinking also that there's optionality in building all this capacity right now, in case something happens with China, right? So there's all this competition from China, but say that. Something happens with Taiwan. Something happens, whatever, right? The relations between the US and China get even more strained and all of the restrictions export bans and all that, they get brought into not only leading edge and AI stuff, but all kinds of other stuff.

It would be great for Texas Instruments to have all of this fabbing capability in the US at that time, right? If a big competitor goes away. I would tend to trust them to. Invest stuff that's going to get a good ROIC. Maybe Elliot has a point that it could be more flexible about it, but there are such long lead times with everything and inertia, that's not the kind

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: can turn on a dime anyway.

MBI: Yeah. I'm not sure whether I mentioned this, but I just do want to disclose that I do own Texas Instruments, in my portfolio. But I totally agree that, Texas instrument does have that optionality. Like, if something really, that tail event that you are talking about, I think text instrument is probably going to be very few beneficiaries, if such a tail event, comes to fruition.

it, again, it doesn't even have to be a total invasion, like you are saying. Even the, relationship between China and US, if it just continues to deteriorate,

Liberty: on Chinese chips, or it could

MBI: Yeah. Right. If it just continues to deteriorate, that can itself be enough, for companies to retreat from China and like, you know, be even more reliant on Texas Instruments.

And again, like, you know, they are building their inventory. They, I think the inventory on days went from like 110, 120 to 190. So they are definitely building the inventories. If something happens. they will be able to deliver it quickly, and I think are also expanding their capacity even more, so the extent that the relationship between China and the U.

S. deteriorates and to the extent, China's probability of invading Taiwan increases, the perception increases, then I think, Texas Instruments is probably going to be a beneficiary of that.

Liberty: I'm doing this way backwards, but I think for those who are not familiar with Texas Instruments, want to give an overview of what they do, what makes them special. this is a pitch if that sounds interesting and you want to know more, like go subscribe to MBI Deep Dives and read, the whole thing.

There's a lot more in there. But what's cool about Texas Instruments and Analog Devices is similar, is that they're, they're specializing in analog chips. What that means is, most of the chips that we hear about, the really sexy ones, like a CPU or GPU, NVIDIA, Intel, they deal pretty much entirely with, digital signals, right?

Ones and zeros coming on one side, some logics, whatever, something happens to those ones and zeros, they come out on the other side, something happens. With analog chips, you're dealing with, What you could describe as the real world, right? So there's a temperature sensor, a speed sensor, a pressure sensor.

There's a radio wave signal coming through an antenna, and you have to take that analog signal from the real world and then convert it to digital, or maybe do something analog to it too, make something happens with that analog signal. And a lot of those chips, like Texas Instruments has thousands and thousands of SKUs and different products.

MBI: Yeah. I think 80, 000, something

Liberty: Yeah, it's, it's, it's insane. Right. And, and they're selling a lot more of them directly now on TI. com. They, they've been around

forever. So they have the two letter domain name. and so all of these chips that they sell, a ton of them are like 50 cents, 75 cents, a couple of bucks, right?

They, they don't have a big sexy, like, the new Ryzen by AMD or, or the new Hopper or, whatever, right? They don't have that stuff. But this super long tail of chips, they're hard to make in the first place, but once you design it, can sell it pretty much forever and it gets designed stuff by engineers.

So you make a washing machine and some engineer is going to look at a catalog of parts and they're going to design in like 10 chips by Texas Instruments, right? So if a competitor wants to come in and compete on one of these chip, it's maybe investing like maybe millions of dollars to recreate that chip that they were going to sell for a dollar.

Right. It's, it's very, very hard to compete with that kind of catalog and it's still done. And some of those chips, like it's worth it and, our higher volume and higher price and all that. But there's still this, huge long tail that once someone does it, there's probably very little reason for a competitor to offer a second, variant

MBI: Very hard. Even for incumbents, like if Texas Instruments wants to take share from analog devices, like, in the next couple of years, it's going to be super difficult. Part of the reason why, analog devices, you know, Decided to acquire a bunch of companies over the last like five, seven years because even for the analog devices, you know, the nearest competitor of, Texas Instruments, again, full disclosure, I also own Analog Devices.

So, for them to, participate in this kind of, in a growth story of, industrials and automotive segments. And they have to basically acquire a couple of companies in a Linear technology and Maxim integrated, right? they did like, over the last I think five to seven years they acquired this couple of companies now.

They are like, they're almost at similar size of Texas I think they're like at 70 75 percent of Uh, Texas Instrument Size, they used to be like at 20 percent size, like 10 years ago, but thanks to these acquisitions, they are now almost, getting closer to Texas Instrument Size. I couldn't really figure out what's the overlap between these two companies,

Liberty: Yeah. I wish I knew That too.

MBI: yeah, could be the case they are just, you know, going for separate sockets and like, you know, separate devices and like, you know, uh, instruments, hard to figure out what's the exact overlap, but they are, you know, Analog Devices and Texas Instruments are definitely competitors.

Analog Devices are actually explicitly mentioned that I think roughly 5 to 10 percent of their, revenue comes from chips that were designed like before 2000. Right. they're still getting revenue from the chips.

Liberty: like 200 years old.

MBI: Yeah, exactly. Absolutely. Right. So, that's part of the reason why I really like this industry, I think the ROI on the R& D is just so much higher, right?

Like, you know, because you can just, enjoy, uh, The fruits of that R& D for

years and years, decades, right, later. On the other hand, like, you know, the digital chips, the logic chips, like

Liberty: is harder to design. It's way harder to design. And

MBI: Yeah.

Liberty: later, it's in the bargain bin somewhere and nobody wants it.

MBI: Right, and then the next thing comes along and then you do that again. So, it's a more like Red Queen's race, I feel like,

when it comes to the CPUs and GPUs of the world. even like, NVIDIA is talking about like, you know, launching something every year, right?

Liberty: different chips and like,

MBI: yeah, incredible. Like, so, yeah, it's great.

It's unbelievable that they are actually executing that. You know, it's, it's, it definitely boggles my mind that they are able, they are being able to execute that kind of time, you know, cycle.

Liberty: yeah, If they miss one or two in a row, that could be terrible. for them. Right.

Liberty: One more bottleneck on competition for the analog players is that Say you look at the company, that, another device is acquired. I don't, I don't remember exactly the valuation, everything, but say you, you think, okay, right.

I could build all of that catalog back for less money than they paid me. So I should grow organically, it's like, where are you going to find all the analog engineers to do that? And how long is that going to take? it's, it's

MBI: right.